William Bartram, Indigenous Botany, and the Roots of American Medicine

Eighteenth century American medicine was closely tied to botanical knowledge. While the Bartrams’ contribution to early American medicine through their relationships with physicians in Philadelphia is well-documented, what is less discussed are the ways that John and William Bartram preserved Indigenous knowledge about the medicinal properties of various plants.

From the start, medicine in the colonies was markedly different from practices in Europe. Formally trained physicians already had a dubious reputation in Europe and were only scarcer and more expensive in the Americas, and their imported medicines were constantly in short supply. Medical science was, at best, imprecise, and at worst actively harmful to patients who came down with sickness. Most care was instead outsourced to apothecaries, who stocked their shelves with plants not native to the Americas and concocted recipes used to treat all sorts of ailments, from common colds to venereal diseases to tropical diseases like yellow fever. And without any knowledge of the strange and new plants they encountered in the region, apothecaries and commoners alike often turned to Indigenous people for care or otherwise sought cures from their medical botanicals.[1]

Needless to say, the often-improvised reality of medical treatment in America did not conform to the theories of the country’s most-remembered physicians. Two prominent Philadelphia physicians, Dr. Benjamin Rush and Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton, wrote treatises that attempted to organize this rudimentary system of medical treatment, but generally excluded the original context that the remedies they described were discovered within. Those physicians had an economic incentive to appropriate Indigenous remedies while simultaneously disavowing their usage by Indigenous healers, since they would have competed directly with them for patients.[2] As a result, the contributions that Indigenous botanical knowledge made to early American medicine is usually underemphasized, but the writings of William Bartram preserve some of that history.[3]

Recent scholarship has suggested we should understand early American medicine as part of a distinctive “Atlantic World medical complex” which “melded people, plants, and knowledges” from Indigenous, African, and European sources.[4] Cures from Europe were widely used in this context, but so too were remedies that had their roots in the medical systems of the Lenape or Cherokee, and remedies that reached Euro-Americans through the African diaspora.[5] By tracing references William Bartram makes to Indigenous medical botany in his writings, we can reconstruct the Indigenous roots of early American medicine that have been left out of the record by authors like Barton and Rush. Bartram’s journey across the lands of the Creek and Cherokee in the southeastern part of the country, published in his literary classic Travels and other correspondences, offers a rich look into the medicinal world of those groups:

Indigenous Medical Botanicals described by William Bartram [6]

| Bartram’s Name | Modern Name | Medicinal Use |

| *Bignonia crucigera | Bignonia capreolata, cross-vine | Attenuate and purify blood, treating yaws |

| *Casine Yapon | Ilex vomitoria, yaupon. | Cathartic |

| Chaptalia tomentosa | Chaptalia tomentosa, pineland daisy | Vulnerary and febrifuge |

| *Collinsonia | Collinsonia canadensis, richweed, horse balm | Febrifuge, diuretic, and carminative |

| *Convolvulus Panduratus | Ipomoea pandurata, man of the earth | Dissolvent and diuretic; nephritic complaints |

| *Erigeron Puchellus | Erigeron pulchellus, robin’s plantain | Antidote to poison and snakebites |

| *Iris versicolor, Iris verna | Iris versicolor, blue flag | Cathartic |

| *Laurus, bays | Persea borbonia, red bay | Attenuate and purify blood, treating yaws |

| *Lobelia siphilitica | Lobelia siphilitica, great blue lobelia | Antivenereal |

| *Mitchelia | Mitchella repens, partridgeberry | Nephritic complaints |

| *Nondo, white root, belly-ache root. | Angelica atropurpurea, purplestem angelica | Carminative, relieving stomach disorders, colic, hysteria |

| *Panax gensag | Panax quinquefolius, ginseng | Carminative, relieving stomach disorders. |

| *Podophyllum peltatum, Hypo or May-Apple | Podophyllum peltatum, mayapple or poison mandrake | Emetic, cathartic, and vermifuge |

| * Saururus cernuus, swamp lily | Saururus cernuus, swamp lily or lizard’s tail | Emollient and discutient |

| *Silphinium | Silphium terebinthinaceum, prairie rosinweed | Breath-sweetening, emetic |

| *Smilax | Smilax spp., catbriers. | Attenuate and purify blood, treating yaws |

| *Spigelia anthelme | Spigelia marilandica, woodland pinkroot | Vermifuge |

| Stillingia, Yaw-weed | Ditrysinia fruticosa, Gulf Sebastian-bush | Cathartic, treating yaws |

| Tatropha urens, White nettle | Cnidoscolus urens var. stimulosus, tread-softly, finger rot | Caustic and detergent |

* Indicates a plant that was included in Bartram’s 1807 catalogue of plants at the garden.

Unlike other writers, Bartram’s ethnographic interest in Indigenous societies led him to record the cultural context that many of these remedies were used in. Euro-American physicians sometimes shared an interest in the specific properties of plants, but Bartram’s commitment to describing the rituals associated with medicine reveals the contours of Indigenous medical systems.[7] The Creek and Cherokee did not confine their treatments to remedies alone, for instance, but usually combined them with “regimen and a rigid abstinence with respect to eating and drinking, as well as the gratification of other passions & appetites.”[8] Sometimes, Bartram describes the preparation of different plants, for example how the China Brier and Sassafras root were combined with cuttings from the Bignonia crucigera vine and boiled to produce what he calls a “Diet Drink.”[9] An infusion of the tops of Collinsonia was “ordinarily drunk at breakfast” and unlike most medicines, this one was of “exceeding pleasant taste and flavor.”

Elsewhere, he recounts the processes the Creek and Cherokee underwent to turn plants into medicines. Podophyllum peltatum, the May-Apple, which Bartram described as “the most effectual and safe emetic and cathartic,” was prepared through digging up the roots in Autumn, drying them in a loft, and reducing them into a “fine sieved powder” that could then be used as medicine.[10]

William Bartram’s illustration of Collinsonia canadensis, horse-balm, ca. 1801-1802. Both John and William Bartram held Collinsonia in high regard as a febrifuge. [Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.]

At the time the town was fasting, taking medicine, and I think I may say praying, to avert a grievous calamity of sickness, which had lately afflicted them, and laid in the grave abundance of their citizens; they fast seven or eight days, during which time they eat or drink nothing but a meagre gruel, made of a little corn-flour and water; taking at the same time by way of medicine or physic, a strong decoction of the roots of the Iris versicolor, which is a powerful cathartic; they hold this root in high estimation, every town cultivates a little plantation of it, having a large artificial pond, just without the town, planted and almost overgrown with it, where they usually dig clay for pottery, and mortar and plaster for buildings, and I observed where they had lately been digging up this root.[11]

Medical texts might list Iris versicolor as a cathartic, but they would not list its role as part of a complex procedure for staving off sickness that Bartram describes. We cannot determine from this description if this medical ritual was replicated across the region, but the fact that “every town” would “cultivate a little plantation of it” indicates that it was among the most important medicinal plants to the Creek and likely carried strong symbolic significance.

The transfer of medicinal knowledge was not always a frictionless process. Indigenous people were acutely aware of the dangers posed by Euro-American settlers in this period, and in one case Bartram recalls the Cherokee nation withholding medicinal information from him:

The Cherokees use the Lobelia siphilitica & another plant of still greater power and efficacy, which the traders told me of, but would not undertake to show it to me under Thirty Guineas Reward for fear of the Indians who endeavor to conceal the knowledge of it from the whites lest its great virtues should excite their researches for it, to its expiration.[12]

Still, William Bartram lists at least four remedies that became widespread among white settlers after being described to them by the Indigenous inhabitants of the region, and as mentioned earlier, white settlers often turned to Indigenous doctors for care.

Two plants that Bartram held in particularly high regard were the Swamp Lily (Saururus cernuus) and the mayapple, (Podophyllum peltatum), the latter of which he attributed to preserving “the lives of many thousands of people of the Southern states.”[13] Bartram himself wrote that he had been treated with it and attested to its “almost infallible good effects”. The mayapple, known as highly toxic both to Europeans and Lenape people in the Northeast, was used by the Cherokee and Creek to expel worms, and as an emetic (to induce vomiting), and a cathartic (a laxative).[14] Swamp Lily could be used to treat wounds or fight fevers. The virtues of both plants, Bartram recounts, “were communicated to the White inhabitants by the Indians.”[15] Etoposide, a chemical derived from Podophyllum peltatum, remains a widely used medicine in chemotherapy treatments today.[16]

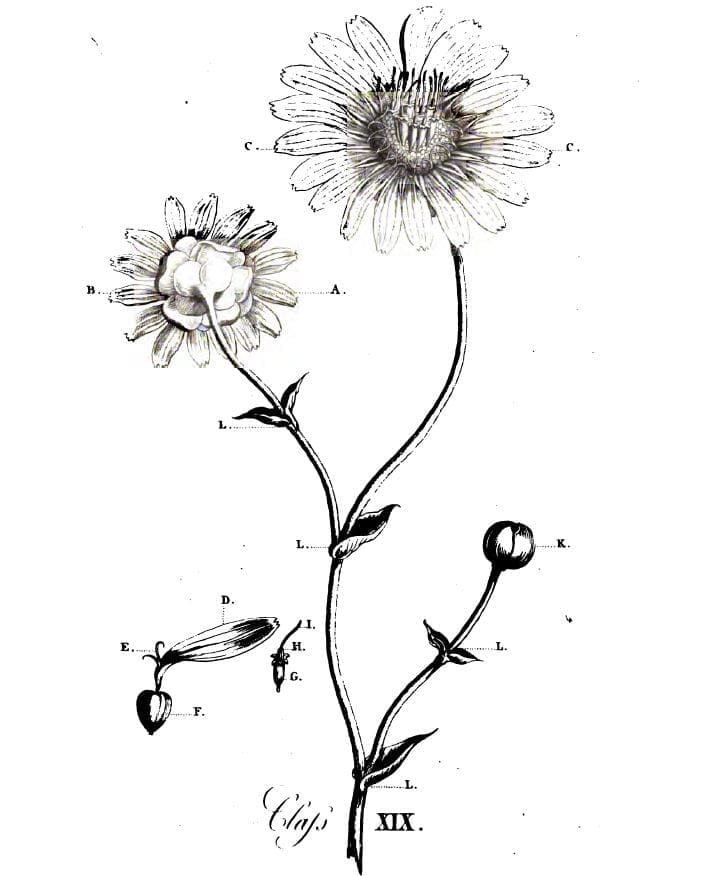

William Bartram’s drawings medical botanicals were renowned for their accuracy and beauty. Members of the American Philosophical Society commissioned drawings of his plants for their research. This drawing is of Podophyllum peltatum, the mayapple, ca. 1801-1803. [Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.]

William Bartram’s writings contributed to both the preservation and appropriation of Indigenous medical knowledge. In a very direct sense, the Bartrams commodified and perhaps profited off of the Indigenous cures they encountered. But William Bartram’s writings also preserved the Indigenous roots of early American medicine, when other sources have obscured or willfully suppressed them. William’s expeditions and careful observations of Indigenous medicine made Bartram’s Garden into an important node in the transatlantic exchange of medicinal knowledge and reveal the global and contested roots of modern medical science.

Notes

Cover image: William Bartram’s drawing of Silphium terebinthinaceum, rosinweed, engraved for publication in B. S. Barton’s Elements of Botany, Philadelphia: 1803.

[1] Ray, Laura E. “Podophyllum peltatum and observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians: William Bartram’s preservation of Native American pharmacology.” The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. vol. 82,1 (2009), 31.

[2] McCulla, Theresa. “Medicine in Colonial North America,” Colonial North America at Harvard Library Project, 2017.

[3] Ray, “Podophyllum peltatum,” 29. Ray has shown how Barton’s writings borrowed or even plagiarized many of William Bartram’s observations on medicine in his Collections for an Essay towards a Materia Medica of the United-States, omitting reference to the Indigenous context that Bartram found his plants in. Rush openly dismissed the idea that Indigenous sources could offer anything to Euro-American physicians, writing that “we have no discoveries in the materia medica to hope for from the Indians in North-America” (Cited in Robinson, “New Worlds, New Medicines”).

[4] Schiebinger, Londa L. Secret Cures of Slaves: People, Plants, and Medicine in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World, (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2017), 3.

[5] See our blog post on Cleome gynandra, an African plant that William Bartram found in Louisiana.

[6] This table compiles descriptions from four sources:

Bartram, William. “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians.” In William Bartram on the Southeastern Indians, ed. Gregory A Waselkov and Kathryn E. Holland Braund, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995),161-164.

—The Travels of William Bartram, Naturalists Edition, annotated by Francis Harper, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1958), 207-288.

—Travels in Georgia and Florida, 1773-1774: A Report to Dr. John Fothergill, annotated by Francis Harper, (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1943).

— “William Bartram’s ‘Remarks’ descriptive specimens he sent to Dr. Fothergill and Mr. Barclay,” 1774, in William Bartram: Botanical and Zoological Drawings, 1756-1788, ed. Joseph Ewan (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1968), 154-168.

[7] Robinson, Martha. “New Worlds, New Medicines: Indian Remedies and English Medicine in Early America,” Early American Studies, vol. 3,1 (2005), 97.

[8] Bartram, Observations, 162.

[9] Bartram, Observations, 163.

[10] Ibid., 163. [Podophyllum or mayapple can be fatally poisonous, do not try this at home.]

[11] Bartram, Travels, 276.

[12] Bartram, Observations, 163.

[13] Ibid., 163.

[14] The Pennsylvania Moravian missionary John Heckewelder (1743-1823), who spent years writing about the Lenape, includes the May-Apple on his list of their medical botanicals, but only references its toxicity. John Gottlieb E. Heckewelder, Names of various trees, shrubs & plants in the language of the Lenape. (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1815)

[15] Ibid., 164.

[16] The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, “Etoposide”. Reviewed on Jun 29, 2021. Drugs.com, https://www.drugs.com/monograph/etoposide.html.

[17] Many of these plants are still cultivated at the garden today. These include Angelica atropurpurea, Bignonia capreolata, Collinsonia canadensis, Erigeron pulchellus, Ilex vomitoria, Iris versicolor, Panax quinquefolius, Persea borbonia, Saururus cernuus, Silphium terebinthinaceum, and Spigelia marilandica.