John Bartram’s Journey to Onondaga, 1743

In July of 1743, Conrad Weiser, Pennsylvania’s interpreter and diplomat for Native American nations, invited John Bartram and land surveyor Lewis Evans to accompany him to the Iroquois capital of Onondaga. Weiser’s journey was in response to a conflict that had arisen the previous December, when a group of approximately three dozen Iroquois marched through Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley to attack their rivals, the Catawbas. As winter approached, the party went scavenging for food, shooting at a number of deer and killing at least one pig. A fact likely unbeknownst to them, however, was that these animals were the free-ranging private property of nearby white settlers. Tensions between the groups flared, and a skirmish erupted, which resulted in casualties on both sides. Who provoked the first shots remains debated.[1]

Weiser’s July expedition was on behalf of Virginia’s governor to officially restore peace between the two sovereignties. For Bartram, the opportunity to travel to Onondaga was exciting. Not only did the journey provide him with the chance to collect new assortments of plants for personal and commercial purposes, but according to a letter he sent a week before his departure, it served to “afford us A fine opportunity of many Curious observations,” likely also referring to the region’s picturesque landscapes and sparsely documented Iroquois.[2]

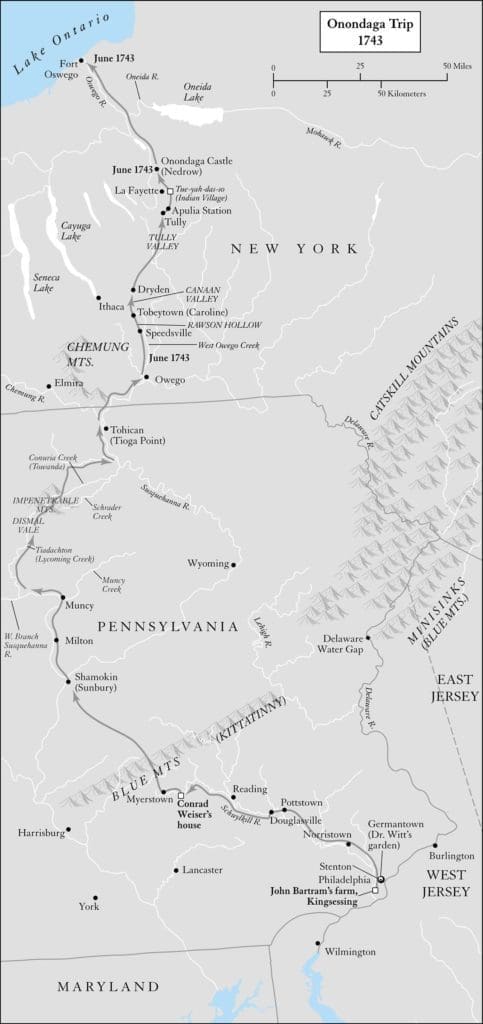

The party departed from Philadelphia on July 3, 1743, first traveling west, then up the Susquehanna River to the town of Shamokin. There, they met with an Iroquois leader, Shickellamy and his son, whose company guaranteed their safe passage. Subsequently, they traveled north along various rivers and valleys, eventually reaching Onondaga on July 21. While Weiser began negotiations with the Iroquois, Bartram and Evans traveled further north to Oswego on Lake Ontario to explore and obtain provisions for their way home. They returned to Onondaga on the 27th, in time to witness the final days of the proceedings, which concluded in peace. The party then returned home on approximately the same route by which they came, reaching Philadelphia on August 19.[3]

John Bartram’s Route to Onondaga, 1743, in Nancy E. Hoffmann and John C. Van Horne, eds., America’s Curious Botanist: A Tercentennial Reappraisal of John Bartram 1699-1777 (Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 2004).

Bartram kept a journal during his journey and sent a copy of it to his English business partner, Peter Collinson, who later had it published in London in 1751. Bartram did not plan for the account to be publicized, so its response was met with mixed reviews.

Those interested in the region’s botany and Bartram’s expertise on the subject were left fairly disappointed. While he does briefly mention finding a massive magnolia tree [Magnolia acuminata] and various other specimens, his account of the region’s flora is surprisingly sparse. The Swedish botanist Peter Kalm criticizes him on this, asserting that “he is to be blamed for his negligence…. He has not filled it with a thousandth part of the great knowledge which he has acquired in natural philosophy.” One private letter written by Bartram during the trip provides a potential insight into the absence. It states, “I have been taken off from viewing the agreable Phenomina of the beautiful varieties in Nature to the Disagreable phenomina of mens perverse Actions,” making it possible that the negotiations fully occupied his mind.[4]

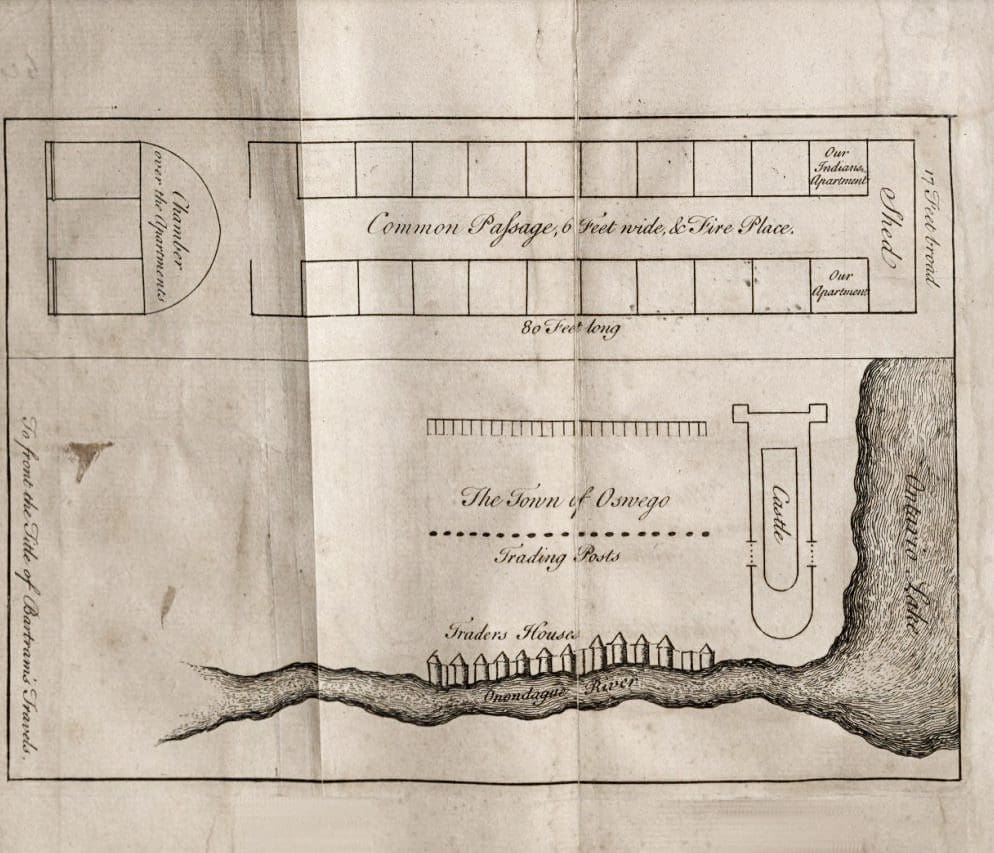

Nevertheless, for readers interested in an adventure story about indigenous lands and cultures, Bartram’s account was just as captivating and insightful then as it is today. Bartram’s description of Onondaga is considered by scholars to be one of the best sources detailing the capital during the mid-eighteenth century. The Iroquois were well known for their communal longhouses, where large numbers of families collectively resided, but after decades of war and disease outbreaks, Bartram painted a very different picture. He described the town as “2 or 3 miles long, yet the scattered cabins on both sides [of] the water are not above 40 in number,” many of them holding two families at most. Although Bartram and his party resided in a longhouse “80 feet long,” it seems it may have been one of the only ones left in the town, with its use being reserved for ceremonial and diplomatic purposes. European colonization efforts had clearly altered portions of the Iroquois’ communities. [5]

Bartram also recorded a number of Iroquois customs and legends on his journey, including a sweat lodge ceremony and the use of tobacco as an offering to appease the spirits of animals after a hunt. This kind of information would have been fairly novel and exciting to people reading in Bartram’s time, but for modern readers, it also provides a glimpse into Bartram’s perspectives towards indigenous populations. While Bartram expressed his gratitude on a number of occasions, he considered Native Americans to be very “superstitious” people, with their legends merely being “silly stories”. More condemning was his view on land ownership. While he described the Iroquois as the Great Lakes’ “original inhabitants,” he contended that the indigenous and French failure to properly cultivate the land “must entitle the crown of Great Britain to all North America.”[6]

As a typical Enlightenment thinker, Bartram’s fascination with the Iroquois was, unfortunately, one of marveling at a lesser “curiosity” rather than an interest in an equal people. It is likely that his prejudiced views were influenced by the Tuscaroras in 1711, who killed his father during their larger war in North Carolina, but such close-minded views were also not uncommon amongst colonists. It is worth considering how the language barrier may have affected his ability to directly amend his views, but Bartram, nevertheless, exemplified the same mindset as the white expansionists who pushed Native Americans westward. It was the same indigenous peoples who, he wrote, had little right to the land that, simultaneously, guided, protected, and hunted for his travel party. Ironically, it is also the Iroquois who retain a portion of their original territory today.[7]

Featured Image: John Bartram’s Sketch of an Onondaga Longhouse (top) and Oswego (bottom), in John Bartram, “Observations of the Inhabitants, Climate, Soil, Rivers, Productions, Animals, and other matters worthy of Notice” (London: J. Whiston and B. White, 1751): 9, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/196084#page/9/mode/1up.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Notes

[1] James Patton to William Gooch, Dec. 23, 1742, in B. Scott Crawford “A Frontier of Fear: Terrorism and Social Tension along Virginia’s Western Waters, 1742-1775.” West Virginia History 2, No. 2 (Fall 2008): 1-29; Warren R. Hofstra, The Planting of New Virginia: Settlement and Landscape in the Shenandoah Valley (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2004): 14-49.

[2] Whitfield J. Bell Jr., introduction to A Journey from Pennsylvania to Onondaga in 1743, by John Bartram, Lewis Evans, and Conrad Weiser. (Barre: Imprint Society, 1973): 7-18; John Bartram to Cadwallader Colden, June 26, 1743, in The Correspondence of John Bartram: 1734-1777, edited by Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992): 218-219.

[3] Bartram, A Journey, 10-11.

[4] Bartram, A Journey, 10-15, 81.

[5] Ibid, 56-59; Daniel K. Richter, The Ordeal of the Longhouse: The Peoples of the Iroquois League in the Era of European Colonization (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992): 257-262.

[6] Bartram, A Journey, 43-51, 54, 67-68.

[7] “Historic American Landscapes Survey, John Bartram House and Garden (Bartram’s Garden), HALS No. PA-1, History Report,” MS report, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, HABS/HAER/HALS/CRGIS Division, Washington, DC, 18.