The Bartrams, the White Mulberry Tree, and the Story of American Silk

The Bartrams were a family of natural scientists who would happily collect and cultivate almost any plant, but they were not immune to acquiring plants that carried the allure of exorbitant profit. Few plants captivated the imagination of eighteenth-century colonists more than Morus alba, the white mulberry tree, famous for being the preferred food of silkworms. The Bartrams played a role in the story of silkworm cultivation in America, which is one defined by fits and starts and grand plans never realized.

Silk’s importance to the early modern economy cannot be understated. Elites in Europe had long preferred silk garb, leading Britain and France to develop highly profitable silk weaving industries by the early 1700s.[1] Gathering raw silk from silkworms, however, proved much more difficult. Growers in Spain and Italy had some success raising silkworms, but most raw silk used in Britain and its colonies was imported from Asia, which along with tea and porcelain, formed the bulk of the East India Company’s lucrative China trade.[2]

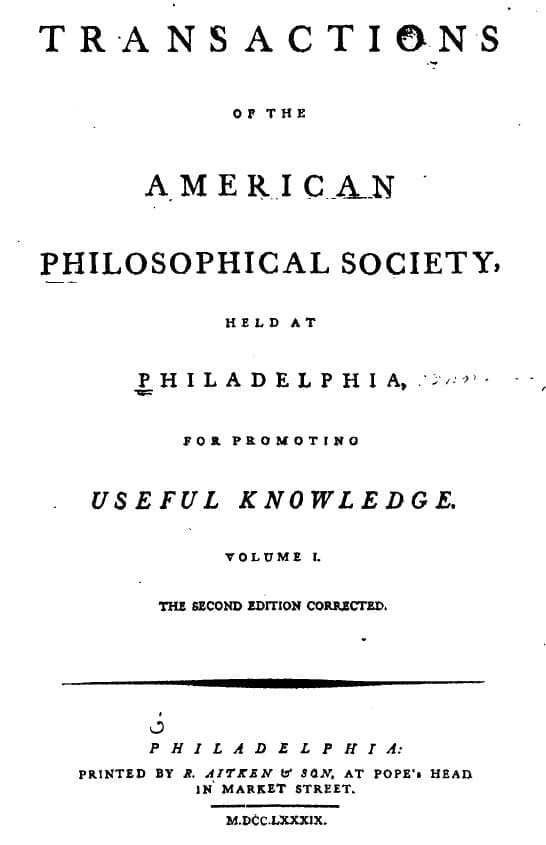

The British were fascinated by the possibility of producing raw silk domestically. King James I developed a plan for growing silk in the Virginia colony as early as 1609. [3] They imported Morus alba trees in pursuit of this project, but the trees quickly escaped cultivation, becoming widespread in the countryside and hybridizing with native red and black mulberry trees. John Bartram reported M. alba growing wild in local forests by the 1750s.[4] The American silk industry never took off as tobacco and cotton were far more lucrative for most farmers. Still, the idea would continue to circulate in the colonies throughout the eighteenth century.

An illustration of the white mulberry tree (Morus alba).

The Bartrams were aware of these experiments in raising silkworms. In 1743, John Bartram received word from the naturalist and politician from New York, Cadwallader Colden, about the governor of Connecticut who was “cloathed in a good handsom Silk of his own making” and had plans to produce one hundred more yards of silk later in the year. Bartram replied and informed Colden of a previous misadventure in silkworm production:

Severall in our province made an attempt to raise Silk about 16 or 18 year ago but the trouble in raising the worms & winding the silk Soon discouraged them & the persons that was the most eager to promote it hath since found a greater profit in raising Hemp & Tobaco so that now we have no inclination to try any farther experiments of the Silk worms notwithstanding our plantations is full of mulberry trees… But if our Neibouring colonys should Succeed its very Likely Some would make another tryall[5]

Despite the failure described by Bartram, the allure of silkworms remained and further trials were indeed attempted. Bartram recognized that the “mighty Monarchs of China” became “so rich and their Princes So Powerfull” through raising silkworms.[6] Silk production would continue in Connecticut over the next few decades, and in the 1760s it piqued the interest of Benjamin Franklin, who organized the immigration of silk workers from England to Pennsylvania. Soon, Pennsylvania and its neighboring states had fledgling silk industries.[7]

The Bartrams enter the story of American silk production again a few years later. John’s son, Moses Bartram, evidently took an interest in collecting silk from native silkworms and experimented with raising them himself. He prepared his observations and delivered them to the American Philosophical Society in 1768. In his remarks, Moses describes capturing five cocoons from local moths in 1766, which gradually hatched and produced moths that laid some three hundred eggs.[8]

The following spring, Moses set to work raising the silkworms. He placed them in glass bottles, put the bottles in the shade to shield the worms from the heat, and filled the bottles with water and vegetables. Moses tried feeding them mulberry leaves, which his native worms apparently did not appreciate, instead preferring to graze on local vegetables (especially apple tree leaves). He wrote down his observations on the worms every week, recording their habits—they crawled down from their perches to “drink heartily two or three times a day”—and their life cycle. By August 10th, they were all wrapped up in cocoons again, where they would wait to emerge next year.

Moses did not report trying to extract silk from the cocoons. He likely did not know how or did not have the instruments to do so. But he hoped that his experiments would reveal how silkworms could be “raised to advantage, and perhaps, in time, become no contemptible branch of commerce,” and compared his worms favorably to those from the East.

Moses Bartram likely raised polyphemus moths, (Antheraea polyphemus) which can still be found at the garden today, like this one spotted a few years ago.

The Bartrams’ experiments with silk production were not over. In spring 1771, we have evidence that Elizabeth Bartram, daughter of John, younger sister of Moses, and William Bartram’s twin, was raising silkworms at their home. John writes to Franklin to inform him of this development, saying that she “hath saved several thousands of eggs of silkworms which she expects will hatch in A few days… she intends to give them A fair tryal this spring.” Franklin was delighted to hear this and replied, wishing her success, adding that “nothing is wanting to our country for the produce of silk, but skill; which will be obtained by persevering till we are instructed by experience.”[9] We know little of what happened to Elizabeth’s experiment in raising silkworms, but they may have been grown in bins in a room attached to the kitchen at the Bartram home in Kingsessing.

Why did silk production not take off in America despite many colonists’ best efforts? Franklin was right that acquiring the skill to grow silkworms was a major obstacle to building a silk industry in America, but there was an even bigger barrier: labor. Raising silkworms was notoriously labor-intensive. Silkworms have to feed for weeks. Once they spin their cocoons, the silkworms are boiled, their cocoons extracted, and then wound on a reel to produce usable fiber. More than two thousand silkworms are required to produce just one pound of silk.

In the American colonies, which were sparsely populated compared to Europe, to say nothing of China and India, finding enough labor to produce a competitive silk industry was a challenge that proved impossible to overcome. Pehr Kalm, a Swedish botanist and traveler who worked under Linnaeus and visited John Bartram, recognized this issue. In his treatise on North American mulberry trees, he commented that “the country was so sparsely inhabited,” that it would be “utterly useless to engage in silkworm culture and the additional work of spinning the silk.”[10] Countless other crops turned a far greater profit, and flax, hemp, and cotton could produce any fibers the colonists needed with far less effort.

Experiments with silk would continue. Around the Revolution, a “silk craze” and swept over the nation as people “gave themselves over completely to the cultivating of silk.”[11] That craze was evident during William Bartram’s travels across the southeastern states, where he describes encountering “a large orchard of the European Mulberry trees (Morus alba), some of which were grafted on stocks of the native Mulberry (Morus rubra) these trees were cultivated for the purpose of feeding silk-worms (phalaena bombyca).[12]

Growers were caught up in a similar craze in the 1830s, when thousands scrambled to buy the recently introduced “Chinese Mulberry” (Morus multicaulis).[13] Like previous experiments, these attempts at raising silkworms domestically could not produce silk efficiently enough and did not amount to much, except a bubble and bust in the nursery trade. Eventually, however, the refining of raw silk became a major industry in the United States. By the end of the nineteenth century silk mills (usually relying on imported raw silk from Japan) popped up all over the country, and in 1920 the silk industry had become the largest industry in Pennsylvania. Silk was a dominant industry in the Eastern states until World War II, when wartime interruptions on imported silk and new synthetic fibers gradually made it obsolete.

White mulberry trees still grow at Bartram’s Garden today, like this one growing just in front of the Bartram house. Photograph by Gabriel Morbeck.

White mulberries remained in the Bartram catalogue for years after their attempts at raising silkworms. In the 1828 catalogue, mulberries are listed available as “small trees of the white Italian or Persian Mulberry, for Silk-worms.”[14] Robert Carr, then the proprietor of the garden, took out an advertisement for the garden’s stock of M. muticaulis in a Delaware County newspaper in 1838. These sales would have undoubtedly enticed the countless ordinary people who hitched their fortunes (and their labor) to dreams of silk cultivation. White mulberries remain widespread around Philadelphia, a reminder of this intriguing piece of our region’s history.

Notes

Cover image: title page from Moses Bartram’s article in the Transactions of the APS.

[1] Leanna Lee-Whitman, “The Silk Trade: Chinese Silks and the British East India Company,” Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 17, No. 1 (Spring, 1982), pp. 21-41

[2] Ronald C. Po, “Tea, Porcelain, and Silk: Chinese Exports to the West in the Early Modern Period,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. (Oxford University Press: 2018).

[3] Cora E. Lutz, “Ezra Stiles and the Culture of Silk in Connecticut,” The Yale University Library Gazette, Vol. 58, No. 3/4 (April 1984), pp. 143-149

[4] Esther Louise Larsen and Pehr Kalm. “Pehr Kalm’s Description of the North American Mulberry Tree.” Agricultural History Vol. 24, No. 4 (Oct., 1950), pp. 221-227

[5] John Bartram, Letter to Cadwallader Colden, September 17th, 1743; in The Correspondence of John Bartram, 1734-1777, ed. Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley (University of Florida Press, 1992), p. 222.

[6] John Bartram, Letter to Colden.

[7] Lutz, “Ezra Stiles and the Culture of Silk in Connecticut”, 144.

[8] The domesticated silk moth, Bombyx mori, has not existed outside of human care for thousands of years, but dozens of its relatives are referred to as “silk moths” and make similar cocoons. Moses described the moth that hatched as a “large brown fly”, which could have been one of the Giant Silk Moths from the family Saturniidae, perhaps Antheraea polyphemus, the polyphemus moth.

[9] John Bartram, Letter to Benjamin Franklin, April 29th, 1771; and Franklin to Bartram, July 17, 1771; in The Correspondence of John Bartram. p. 739, 744. Elizabeth Bartram married William Wright, August 12, 1771 and moved to Conestoga on the Susquehanna in Lancaster County.

[10] Pehr Kalm, “Pehr Kalm’s Description of the North American Mulberry Tree.”

[11] Elizabeth Hall, “If Looms Could Speak: The Story of Pennsylvania’s Silk Industry,” Pennsylvania Heritage, Summer 2006.

[12] William Bartram, The Travels of William Bartram, Naturalists Edition, annotated by Francis Harper, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1958), p. 308.

[13] David Landry. “History of Silk Production,” Mansfield Historical Society, May 6, 2013. Botanists now consider M. multicaulis a variety of M. alba.

[14] Robert Carr, Periodical Catalogue of Frit and Ornamental Trees and Shrubs, Green House Plants &c. Cultivated and For Sale at Bartram’s Botanic Garden, Kingsessing, 1828. Provided through the Library of the New York Botanical Garden.