Plantations in Pennsylvania

Passages taken from “Slavery and Freedom at Bartram’s Garden” by Joel T. Fry, presented at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies conference: Investigating Mid-Atlantic Plantations: Slavery, Economies, and Space, 17-19 October 2019: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The word “plantation” has lost some of its varied meanings in modern US English, with the common colloquial definition now focused down to large-scale agriculture (or industry) with enslaved labor, often implying ante-bellum Southern US plantations. “Plantation” in English derives from action words in Latin or French meaning “to plant” or “a planting” [of crops, trees, even people]. An example of its early 18th century meaning can be gathered from Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia of 1728:

PLANTATION, in the Colonies, a Spot of Ground which some Planter or Person arrived in a new Colony, pitches on to cultivate and till for his own Use. See COLONY.

COLONY, a Plantation, or Company of People, of all Sexes and Conditions, transported into a remote Province, in order to cultivate and inhabit it. See PLANTATION.[1]

In the Cyclopaedia definition, a plantation is essentially part of and similar to a colony. Chambers’ definition of “Colony” is expanded out with three forms of colonies: “The first to ease or discharge the Inhabitants of a Country where the People are become too numerous…; the second are those establish’d by victorious Princes and People, in the middle of vanquish’d Nations… to keep ‘em in awe and obedience. The third may be call’d Colonies of Commerce….” All three of these forms of colony seem to also be found in the efforts of plantations in North America.[2]

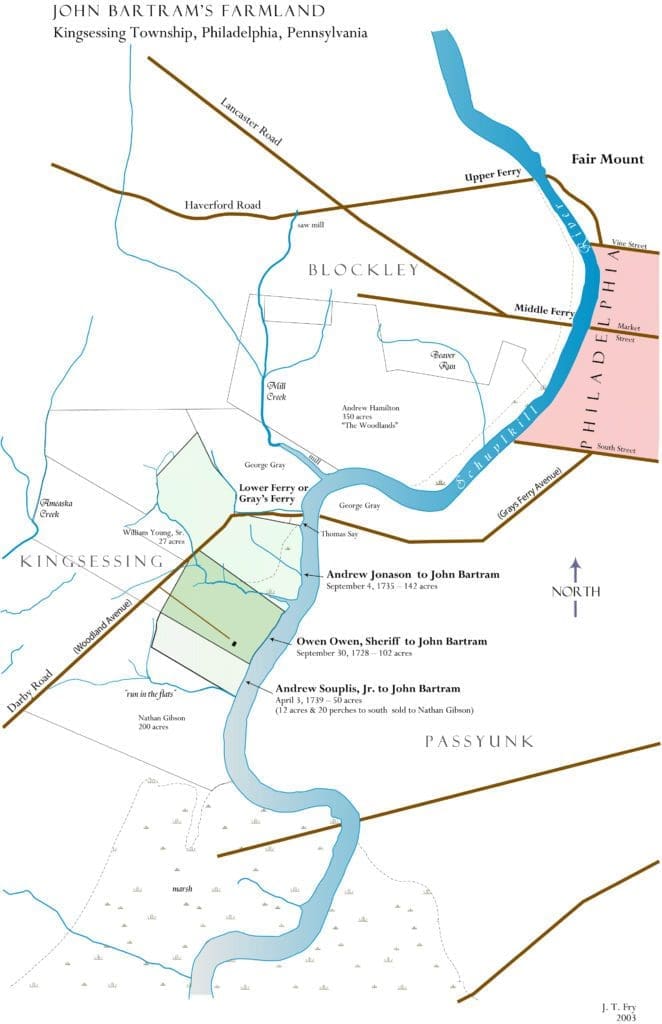

By 1739 John Bartram owned three adjacent farms in Kingsessing totaling close to 3oo acres, and he also retained the ancestral farm in Darby which was around 140 acres. From limited data, Bartram operated these tracts as individual farms, pursuing typical mixed agriculture of the rural areas around Philadelphia — mixing dairying and small number of sheep and horses with wheat and a mix of other small grains and field crops in rotation.[3] The Kingsessing farms were eventually combined into two farms of around 140 acres each with Bartram himself managing one, and an older son James Bartram was given control of one farm at his marriage in 1753. The Bartram family farm in Darby was likely leased or run by a tenant. Mixed farms or plantations in Kingsessing could be operated within the scope of family labor with occasional hired help, indentured labor, and only rarely with limited enslaved labor.[4]

John Bartram and his European correspondents, and particularly his London correspondent Peter Collinson (1694-1768) only occasionally used the word “plantation” and then with several meanings. The Londoner, Peter Collison mainly used “plantation” to mean large agricultural or forestry plantings, generally in Europe, but he also on occasion used it to describe the Virginia tobacco plantations where he had acquaintances.[5]

John Bartram only very occasionally referred to his farm in Kingsessing as a plantation and used farm much more regularly. “Plantation” tends to be used with a vaguely historical sense, referring to when Bartram first settled in Kingsessing:

… the first I observed sloe trees was at a plantation whose owner came two years into this country before A house was builded in Philadelphia I brought some from there when I settled on my plantation.[6]

And notably, John Bartram, retired in 1772, wrote to his son William, then on the Cape Fear River in North Carolina: “I have thrown of[f] all plantation business to John & we live with him.”[7]

In biographical accounts long following the death of John Bartram, his son William Bartram uses “plantation” with some more frequency to describe all his father’s botanical plantings in and around the family farm and garden at Kingsessing. The term appears in the several published versions of William Bartram’s biography of his father that first appeared anonymously in the Philadelphia edition of the Supplement to the Encyclopaedia 1800 and was reprinted little changed in the Cyclopaedia printed in Philadelphia in 1807. William Bartram also published a longer biographical essay on his father in 1804, and included similar biography in the “Preface” to the 1807 Catalogue of the plants at Bartram’s Garden. In each of these biographical pieces, William Bartram uses “plantation” to include both North American plantings at his father’s farm and garden, as well as plantings of American plants in gardens of the European customers of the Bartrams:

he purchased a plantation in a delightful situation on the banks of the Schuylkill, about five miles from Philadelphia, where he laid out, with his own hands a large garden.[8]

And John Bartram’s work was:

collecting whatever was new and curious to furnish and ornament the European gardens and plantations with the productions of the New World.[9]

By the early 19th century date of these filial biographies it may seem William Bartram was using “plantation” as an intentionally nostalgic glance back at the old colonial world. These same biographical accounts of John Bartram by son William are also the major source of evidence that John Bartram freed a slave.[10]

Notes

[1] Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopædia, or, An universal dictionary of arts and sciences: containing the definitions of the terms, and accounts of the things signify’d thereby, in the several arts… 2 vols. London: Printed for J. and J. Knapton… (1728). “Plantation” vol.2, p. 832; “Colony” vol. 1, p. 257. Chambers ended his long article on Colonies with this: “Originally, the Word Colony signify’d no more than a Farm: i.e. the Habitation of a Peasant, with the Quantity of Land sufficient for the Support of his Family.”

[2] It is often stated that “plantation” was a measurement term in the mid-Atlantic for a farm of larger acreage. The current entry on “Plantations,” in the web-based “Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia,” https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/plantations/ uses that exact hierarchy of acreage: “In the eighteenth century the word simply meant a property containing between one hundred and one thousand acres.” While the terms “farm”, “plantation” and “manor” do appear in early descriptions of property and land transactions in Pennsylvania, there is nothing to indicate that “plantation” referred to this precise range of size or scale. “Manor” had a special meaning in purchases from the Proprietor, usually reserved for Penn family relations or extraordinary conditions, and it sometimes conveyed quasi-feudal rights. Plantation seems largely synonymous with farm or perhaps “colonial farm” in early Pennsylvania.

[3] Marsh lands and drained marsh meadows for grazing were also perhaps the most valuable part of the farms along both sides of the lower Schuylkill. From the mid-17th century, considerable community cooperative effort was put into building and maintaining banks and ditches and sluices to drain the marshlands.

[4] There were a few individual cases of farms or plantations with a workforce of 4 or more enslaved Africans in Kingsessing, possibly raising tobacco in the Chesapeake fashion with hand cultivation. Tobacco cultivation had been attempted under the Swedish colony on the Delaware and Schuylkill, following the model of Maryland and Virginia, in part as the Swedish crown granted the colony a monopoly on tobacco imports to Sweden. But tobacco was apparently never a widespread crop in New Sweden, and tobacco was not grown by the Bartram family.

[5] Peter Collinson to John Bartram, March 14, 1737; The Correspondence of John Bartram 1734-1777, edited by Edmund Berkeley, and Dorothy Smith Berkeley. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 1992, p. 41; PC to JB, September 1, 1741; Correspondence of JB: p. 167; PC to JB, ca. March 10, 1744, Correspondence of JB: p. 235

[6] JB to PC, May 1738; Correspondence of JB: p. 89.

[7] JB to WB, July 15, 1772, Correspondence of JB: p. p. 749.

[8] “BARTRAM, (JOHN)” in Supplement to the Encyclopædia, vol. 1, Philadelphia: 1800, p. 91.

[9] Supplement to the Encyclopædia, p. 92.

[10] William Bartram, both anonymously and credited penned several short biographies for his father, the first printed in 1800 was the biographical entry, “BARTRAM, (JOHN),” that appeared Supplement to the Encyclopædia,. vol. 1, Printed by Budd and Bartram for Thomas Dobson, Philadelphia 1800, p. 91-92; and reprinted in 1807 as “Bartram, John,” in The Cyclopaedia, or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature, vol. 4, Philadelphia: 1807, with minor additions by Alexander Wilson. William Bartram also wrote a biographical article under his name for B. S. Barton’s medical journal in 1804. “Some Account of the late Mr. John Bartram, of Pennsylvania.” Philadelphia Medical and Physical Journal, vol. 1, part 1 (1804), p. 115-124. And finally, the preface to the 1807 Bartram catalogue contains a different short version of William Bartram’s biography of his father, A Catalogue of Trees, Shrubs, and Herbaceous Plants, Indigenous to the United States of America; Cultivated and Disposed of By John Bartram & Son, At their Botanical Garden, Kingsess, near Philadelphia. Bartram and Reynolds, Philadelphia: 1807, p. 5-7.