“6 likely negroes”: John Bartram and the East Florida Plantation

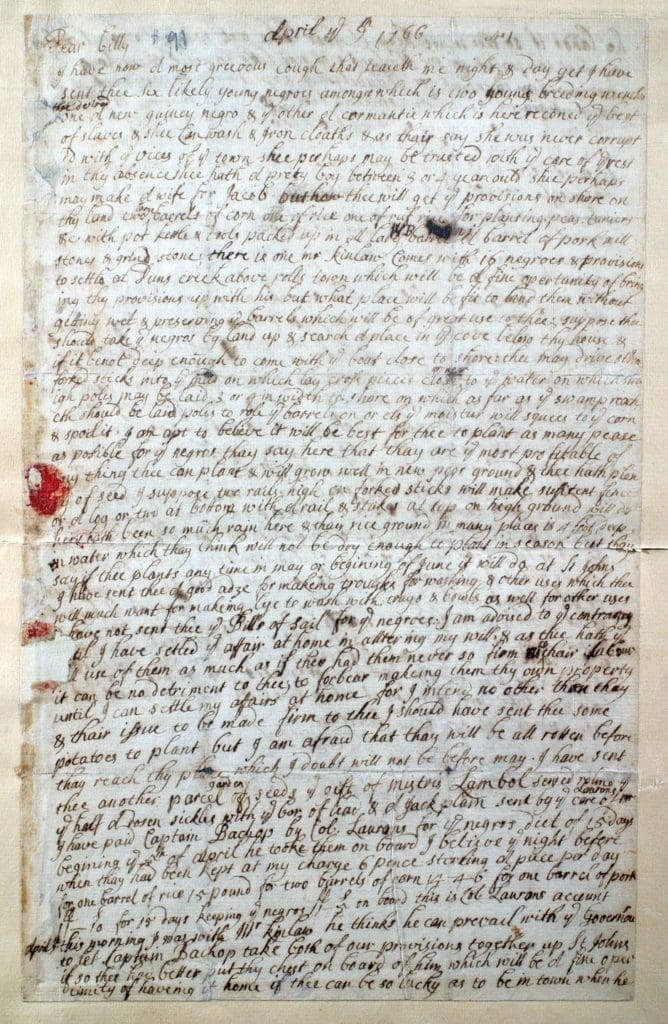

Second letter of John Bartram, [Charleston, SC] to son, William Bartram, [St. Augustine, FL] April 9, 1766, New York Historical Society.

On April 5, 1766, John Bartram wrote a letter to his son about a shipment from Charleston to East Florida. William Bartram became a plantation owner in the British colony to plant rice on 500 acres of land along the St. Johns River. However, William needed his father’s help to finance his new venture. Supporting his efforts, John Bartram purchased six enslaved people in Charleston, South Carolina, and shipped them to William’s East Florida plantation.[1] In John Bartram’s letter to William, he described the enslaved group:

I have shiped on board the East Florida Captain Bachop 6 likely negroes called Jack a lusty man a new negro 5 foot 8 inches high & ¼: Siby his wife new 5 foot one inch ¾ Jacob 5 foot high & Sam 4 foot 7 inches ½ allso Flora a lusty woman not so black as many a cromantee… Bachus her son is a pretty boy 3 or 4 years ould.[2]

John Bartram’s letter to William reveals more than his participation in the slave trade but his attitude towards the people he held in bondage. Immediately after describing the group of people sent to East Florida, Bartram ends his letter the way it began, with a list of items he sent to William. The newly purchased human chattel was casually mentioned between four good yams and a grindstone. In a follow-up letter to William, Bartram reminds his son that he sent him “two young breeding wenches,” referring to Siby and Flora.[3]

Bartram’s use of ‘new’ in his description indicates the amount of time an individual had to acclimate to enslavement. In his letter, he explains that newly imported slaves are preferred since they, “as yet not haveing learnt the mischievous practices of the negroes born in the country and town which the people generally represents as if thay was all either murderers runaways [or] robers, or theeves; espetially the Plantation negroes.”[4] During the purchase process, John Bartram relied heavily on the advice and assistance of friends in Charleston who already owned people. Historians have found no archival evidence that Bartram ever manumitted the people he sent to East Florida. Further research is required to locate them in the historical record. The way scholars write about historical figures has evolved with the field of history itself. The ability to present a transparent historical narrative has grown more necessary with time. Early depictions of Bartram and more recent discussions of race and slavery create an opportunity to examine the past through a more transparent lens.[5]

After the failure of his East Florida plantation, William Bartram enslaved “a negro woman named Jenny” from North Carolina before transferring ownership to his brother-in-law, George Bartram.[6] Later in life, William wrote extensively of his opposition to slavery. Archival documents certainly support an argument for antislavery advocacy among John Bartram’s descendants. And still, John Bartram purchased six people. Building a complete narrative is imperative for posterity, credibility, and accountability. More importantly, we owe it to Jack, Siby, Jacob, Sam, Flora, and Bachus.

[1] “Letter from John Bartram, [Charleston, SC] to William Bartram, St. Augustine, April 5, 1766”, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Bartram Family Papers (Collection 36), Box 1, folder 62. This letter is published in the collection of William Bartram’s correspondence, edited by Thomas Hallock and Nancy E. Hoffman, William Bartram, The Search for Nature’s Design: Selected Art, Letters, and Unpublished Writings. (University of Georgia Press, Athens, GA: 2010), pp. 54-56. Quotes from the Bartram letters reproduced here reflect the original and sometimes erratic spelling of John and William Bartram.

[2] Ibid. Note: “Cromantee” is a subgroup of the Akan people from southern Ghana. Joseph K. Adjaye, “Time in the Black Experience”, Issue 167 of Contributions in Afro-American and African Studies, (Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994).

[3] “Letter from John Bartram, [Charleston, SC] to William Bartram, [St. Augustine, FL] April 9, 1766,” New York Historical Society, Miscellaneous Manuscripts Collection.

[4] “Letter from John Bartram to William Bartram, April 9, 1766”, HSP, BP 1:62. Hallock & Hoffmann, eds. William Bartram, The Search for Nature’s Design…, pp. 56-58.

[5] For more information on William Bartram’s failed plantation on the St. Johns River in Florida see: Daniel L. Schafer, William Bartram and the Ghost Plantations of British East Florida. (University Press of Florida, Gainesville: 2010), Chapter 2 pp. 29-38.

[6] This 1772-1773 Slave deed is reproduced in the Hallock & Hoffmann eds., William Bartram, The Search for Nature’s Design…, p. 91, Figure 29. The original document is at the American Philosophical Society. George Bartram (1735-1777) was the Scottish husband of Ann Bartram (1741-1824) referenced in Stories We Know, and father of Philadelphia alderman George Bartram (1767-1840). Joel T. Fry, “Slavery and Freedom at Bartram’s Garden”, pp. 13.