“Harvey’s Grave”

Passages taken from “Slavery and Freedom at Bartram’s Garden” by Joel T. Fry, presented at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies conference: Investigating Mid-Atlantic Plantations: Slavery, Economies, and Space, 17-19 October 2019: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Determining if enslaved or free Black individuals were present on a mid-Atlantic farm is not entirely a straight-forward and simple process. Even determining which members of an extended family were resident on a farm in any given year can be difficult. Tax records that detailed slave or servant labor are generally not available until the last half of the 18th century for the rural townships around Philadelphia, and even then, those records are incomplete and very irregular. Probate records, court records, church or Friends meeting records, and family papers, letters, diaries and even ledgers can also be useful when available. But almost all those sources are either silent or unavailable for the Bartram family (although a large collection of personal letters from John Bartram and his son William are preserved and have been published in modern editions). Currently there is no primary evidence for Bartram family use of slave labor on their farms in Kingessing or Darby, Pennsylvania, and as will be seen, John Bartram has sometimes been held up as an early proponent of emancipation and an opponent of slavery.[1]

It has long been the story from early biographies of John Bartram that he “gave freedom to an excellent young African whom he had brought up, and who continued gratefully in his service while he lived.” This individual, presumably male remains in the shadows of the history of Bartram’s Garden. He was mentioned in several short, early biographies of John Bartram and eventually in 1860 was he connected with a name, “Harvey.” When the last Bartram heirs left the historic garden site in 1850, the grave of this individual was marked in the southeast corner of the garden, near the river. “Harvey’s Grave” remained marked for at least a century more and was generally included among the tourist attractions at Bartram’s Garden, even before the garden became a public park in 1891.[2]

But the same John Bartram who gave freedom to “an excellent young African,” had a half-brother who ran a large rice plantation, Ashwood, on the Cape Fear River in North Carolina with enslaved labor.[3] And the same John Bartram, with moral objections, purchased six slaves in Charleston in Spring 1766, so that his son William Bartram (1739-1823) could patent a plantation in the new British colony of East Florida. Son William’s plantation effort seems to have failed by the end of summer 1766 and there is no documentation for what happened to his enslaved labor force. And of course, almost all the beneficiaries of the Euro-American economy of the 18th and early 19th c. might be considered silently complicit in the world-wide trade in enslaved labor and the commodities produced through slavery.

There is limited historic inference and family tradition that John Bartram, founder of Bartram’s Garden acquired and freed a single slave. The first printed biographical account of Bartram appeared in London in 1782 and mentioned “Negroes” and implied Bartram once owned “slaves” that had been freed. But there are reasons to doubt many of the early biographies and the only tax records available from the period of John Bartram’s life — the 1767, 1769 and the 1774 assessments do not demonstrate any slaves at the Bartram farms (then in operation by John Bartram or his sons James Bartram and John Bartram, Jr.). A single “servant” was taxed for both John Bartram and James Bartram in 1767 and a single “servant” again for John Bartram in 1769.[4]

Later generations of the Bartram family repeated and elaborated the story of a single free Black individual, and as late as 1860 he was first given a name — “Harvey” based on family history or legend. So far it has been impossible to prove if that name “Harvey” is historically accurate, and only a few ambiguous 18th century documents provide support for a Black individual, servant or free in the Bartram household during the life of John Bartram. But there is physical evidence of a grave at Bartram’s Garden, attributed to this free Black individual, “Harvey.” That grave site was marked with a small marble head and footstone in the late 19th century, and it remained marked in the early history of the city park at Bartram’s Garden, perhaps with some marker into the mid-20th century.[5]

Within a decade of the departure of the last Bartram heirs from Bartram’s Garden, Ann and Robert Carr, the story of the “excellent young African” freed by John Bartram or “Harvey” became one of the essential 5 or 6 historical facts repeated about the site and the first John Bartram. Bartram’s Garden had seen nostalgic or “heritage” tourism from the decade of the 1830s during the third Bartram generation. Occasional published pieces and travelers’ letters about the garden in Philadelphia newspapers and national and international press repeated simple facts about John Bartram, his family, and their botanic garden. But at least so far, none of this early nostalgic history of the garden mentions the name “Harvey” or his gravesite at the garden. The limited published sources for the history of the Bartram family and Bartram’s Garden in the 19th and early 20th c. engendered a loop of close repetitions and elaborations of the few available sources.[6]

As noted above, the name “Harvey” first appears in The Bartram Tribute of 1860, an anonymous small local history tabloid printed as part of a local Kingessing church fundraiser. The story of Harvey becomes an even more popular theme in descriptions of the garden after the Civil War and emancipation.

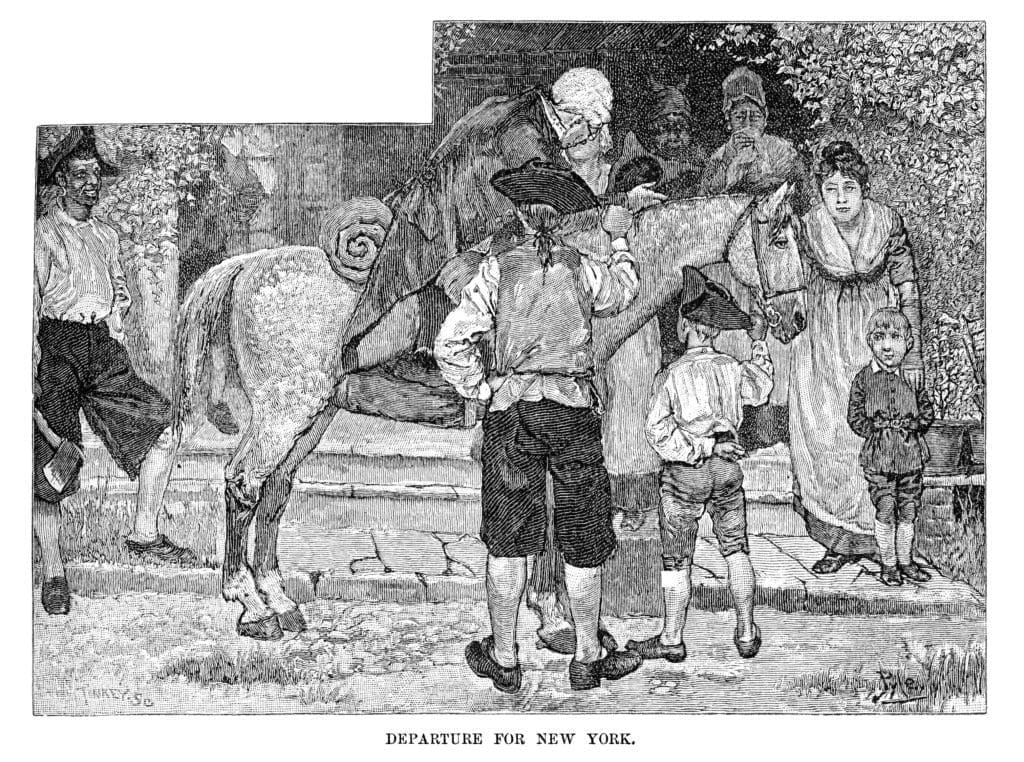

Following the death of Andrew M. Eastwick in February 1879, his widow and younger children abandoned the old Bartram site in Kingessing. There was immediate concern about the future of the historic garden. In Summer 1879 local artist Howard Pyle spent some time at Bartram’s Garden taking notes and making sketches. These were turned into an illustrated article in a national magazine, “Bartram and His Garden” published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in February 1880.[7] Pyle used large quotes from the 1782 Crèvecoeur account of Bartram for his text combined with biographical material from Darlington’s Memorials of 1849.

Not far from the old cider mill stands a stone marking the grave of one of John Bartram’s servants, an aged black, one time a slave, for even the Pennsylvania Quakers had slaves in those days. At the time of the old negro’s death, however, he was a freeman, and had been for years, for Bartram was one of the earliest emancipators of slaves in the colony…

At the death of the old servitor referred to above, he implored “Mars’ John” not even then to remove him from the beloved grounds he had so often tilled, nor from among the trees he had seen growing so lustily beneath his hands; so Mars’ John, laid him to rest beneath the ground where-on he had wrought for so many years, there to sleep his last sleep in peace.[8]

Pyle used Crèvecoeur’s fictional dialogue for John Bartram combined with his own fictionalized personification of the one-time slave, who in this case might have stepped out of the pages of Harriet Beecher Stowe and Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Pyle does not include a name for this individual, and may not have known the name “Harvey,” but he does include an image of the person in his illustration “Departure for New York,” at the far left holding an axe.[9] Pyle’s illustration is the first of many images of Bartram’s freed slave, created for the media and for advertising in the 20th century.

Beginning around 1880 a campaign to preserve the Bartram house and garden was organized with several supporting groups. Thomas Meehan (1826-1901), who had worked as head gardener for Andrew Eastwick at Bartram’s Garden, 1850-1852, went on to a very successful career as a nurseryman and writer on horticulture and botany in Philadelphia. He was interested in the history of Philadelphia gardens, and frequently included bits of Bartram history in the periodicals he edited — The Gardener’s Monthly and later Meehan’s Monthly. Meehan had also frequently brought local and national visitors to the garden. Beginning in 1881 Meehan and Charles S. Sargent, Professor of Arboriculture at Harvard and Director of the Arnold Arboretum organized a group of Philadelphians to purchase the botanic garden from the Eastwick estate by subscription. But the executors of the Eastwick estate withdrew from negotiations and Meehan turned to a political effort to preserve Bartram’s Garden. Meehan entered Philadelphia politics and was elected to the Common Council in 1883, in part with the goal to preserve Bartram’s Garden under city ownership and establish other small parks throughout Philadelphia. By a series of gradual steps from 1884-1891 Meehan succeeded in passing ordinances that allowed the city to take property for parks, and Bartram’s was one of the first parks protected. There was considerable coverage of the political fight to allow for these new city parks and the Philadelphia newspapers of the 1880s and early 1890s are full of articles for and against. The opening of the Bartram Park to the public in March 1891 saw many long, illustrated articles on the new park. Sargent in the pages of his weekly periodical Garden and Forest, a trade paper published in New York dedicated to the business of horticulture and forestry, and environmental preservation also covered the efforts to protect the old Bartram garden in the 1880s and early 1890s.

As with the 1860 “Bartram Tribute,” the story of the faithful freed slave became one of the standard historic facts recited at the garden. There was little or no public interpretation at the house or garden for the first decade of the city park, and the Bartram house was initially closed to the public. It was only opened to the public for a short while ca. 1899-1905, only to be closed again until 1926. The physical grave site at the riverfront was something to see in the early park. The initial 11-acre park, preserved at Bartram’s Garden in 1891 did not actually include the grave site, which sat in the proposed roadbed location of 54th Street on the city plan. At the end of 1896, following a fire that damaged the Eastwick mansion, the city acquired an additional 16 acres which encompassed all the historic botanic garden and the grave site. Early 20th century maps of the city-owned park at Bartram’s Garden plot a rectangle as the location of “Harvey’s Grave” at the southeast corner of the historic botanic garden. The plotted location appears in maps from the Bureau of Surveys and from the Fairmount Park Commission into the middle of the 20th century.

The earliest printed guides of Bartram’s Garden, issued by the John Bartram Association were published in three slightly different editions in 1904, 1907, and 1915. Two different sketch maps with numbered locations were printed — first a simple plan in 1904 largely confined to the area of the 1891 park with 26 numbered trees or locations. Then a much larger map in 1907 with 48 numbered locations was issued and reprinted in 1915. All three of these early guides used similar and familiar text to recount John Bartram freeing his slaves, paraphrasing Crèvecoeur:

Like a true Quaker, he ‘set his negroes free, paid them eighteen pounds a year wages, taught them to read and write, sat with them at table, and took them with him to Quaker meeting; one of his negroes was his steward and man of business, who went to market, sold the produce, and transacted all the business of the farm and family in Philadelphia.’ This faithful servant’s grave is where it should be, — in his master’s Garden.[10]

And the maps in all three versions list “Harvey’s Grave.” at a marked location at the southeast corner of the plan of the garden. Two later updated version of the guide to the garden by Emily Cheston in 1938 and 1953 included no plan, but mention the grave site as an item of interest near the river. “The grave of Harvey — the negro steward to whom Bartram entrusted much of his business, marked by a wooden sign.” was included in 1938 and in 1953 the mention of a marker was removed.[11]

Aside from maps, plans, and guides to the early park at Bartram’s Garden, fanciful images of faithful slave “Harvey” appeared in newspapers, advertisements, and even a calendar from the 1920s to 1950s.

Media images of “Harvey” included a radio play in 1937, part of the DuPont Cavalcade of America, on the CBS radio network. The third Season, Nov. 10, 1937 included the radio drama, “No. 103: John Bartram’s Garden.” Voice actors and an orchestra recreated John and his wife Ann Bartram, and a particularly horrible racist caricature of “Harvey.” The script for this play relied heavily on Crèvecoeur’s dialogue for Bartram from the 1782 Letters of an American Farmer.[12]

It remains difficult to pull apart fact from fiction in the account of the “excellent young African” and the Bartram family’s relations with slavery. But the limited concrete documents, mainly tax records and census records do record a real, if limited Free Black presence at Bartram’s Garden by the end of the 18th century. That single Black individual recorded in the 1790 census might be “Harvey,” but “Harvey” might also be something of a myth? But again the facts of the U.S. census from 1820-1840 do indicate what looks like a small Free Black family living in the Bartram household with the Bartram family. Continued research and local genealogy may someday track down some names for those individuals. “Harvey’s Grave” has not been marked now for almost 70 years, and perhaps should be. While there is no proof the name or the grave site is accurate, if not mythical, it is a plausible story. And it is a physical place to commemorate the early Black history of Kingessing

Notes

[1] The primary editions of the Bartram correspondence are: The Correspondence of John Bartram 1734- 1777, edited by Edmund Berkeley, and Dorothy Smith Berkeley (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992); and William Bartram, The Search for Nature’s Design: Selected Art, Letters, and Unpublished Writings, edited by Thomas Hallock and Nancy E. Hoffmann (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010).

[2] William Bartram’ anonymous account of his father, “BARTRAM, (JOHN),” in Supplement to the Encylcopædia, or Dictionary of Art, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature. vol. 1, Printed by Budd and Bartram for Thomas Dobson, Philadelphia 1800, p. 91-92. While only a single burial was every noted at the site, it is possible a small group or family plot for burials was located there. Late-19th c. photos of the site show a single marked burial.

[3] John Bartram only reconnected in 1760 with his half-brother William Bartram (1711-1770) and family of Ashwood plantation on the Cape Fear River in NC, after a long period of no contact. In 1761 the two half-brothers John and William exchanged sons (both also named William) for education and experience. William Bartram of Philadelphia went south to live with his uncle on the Cape Fear and William Bartram (d. 1770) of Ashwood, NC came north to study medicine and the apothecary business in Philadelphia.

[4] Tenth 18 d provincial tax (1767); twelfth 18d provincial tax (1769), and seventeenth 18d provincial tax (1774). In 1767, George Gray who owned the Lower Ferry property just north of the Bartram farms was taxed for “1 Servant” and “6 Negroes” and his father-in-law James Coultas of Whitby Hall in Kingsessing owned “4 Negros” and “2 Servants.”

[5] The name “Harvey” first appeared in an eight-page newspaper printed for a fundraising event at the St. James Kingsessing church in 1860, on a list of “Garden Relics and Reminiscences” at the end of the paper. There were Bartram descendants (4th or 5th generation from John Bartram) in the neighborhood, but there is no evidence who provided the name. The Bartram Tribute. Published as an Auxiliary Aid to the purposes of the festival given by the Ladies of St. James Episcopal Church, “Bartram Garden,” Kingsessing, June 13 & 14, 1860. Philadelphia.

[6] The major 19th century source for the biography of John and William Bartram and history of Bartram’s Garden was William Darlington’s Memorials of John Bartram and Humphry Marshall, Philadelphia: 1849. Darlington edited a selection of the letters of the Bartrams and Marshall and included a “Biographical Sketch of John Bartram” which largely quoted from and enlarged William Bartram’s 1804 account of his father, including the mention of John Bartram freeing a slave. Darlington also reprinted the text of the full text of Crèvecoeur’s 1782 “Letter IX, From Iwan Alexiowitz…,” Letters from an American Farmer (London, 1782).

[7] Howard Pyle, “Bartram and His Garden.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, vol. 60, no. 357 (Feb. 1880), p. 321-330. This was one of Pyle’s first nationally distributed pieces and Pyle used himself as the model for John Bartram in his drawings.

[8] Pyle, p. 326

[9] Pyle, p. 329. There is a dark face with a kerchief in the center rear of this illustration as well, which could be taken for a stereotyped “mammy” character as well, although not mentioned in any of Pyle’s text. The fact that Pyle mentions the marked grave site, but no name, suggests there was no name or the name was illegible on the small marble headstone and footstone at the grave site.

[10] Elisabeth O. Abbot, Bartram’s Garden, Philadelphia, Pa. John Bartram. The John Bartram Association, Philadelphia: (March 1904); Re-issued with New Plan (August 1907); Third edition (1915). The quote is from the first edition (March 1904), p. 12.

[11] Emily Read Cheston, John Bartram, 1699-1777, His Garden and House William Bartram 1739-1823. The John Bartram Association, Philadelphia: 1938; 2nd edition, revised 1953. The last wooden marker for the grave site seems to have vanished in the 1940s

[12] The Nov. 10, 1937 radio play has been digitized and is available at this link: No. 103 –https://archive.org/details/OTRR_Cavalcade_of_America_Singles/CALV_371110_108_John_Bartra ms_Garden.mp3.