Lenapehoking and Kingsessing: A History

Bartram’s Garden is situated on what was originally the wider territory controlled by the indigenous Lenni Lenape. This territory was referred to by the Lenape as Lenapehoking, which encompassed modern-day central and southern New Jersey, eastern Pennsylvania, and eastern Delaware. The Lenape were primarily concentrated along the Delaware River, which they referred to as Lenapewihittuck, to take advantage of its naturally arable landscape and rich fishing grounds. They also traveled into New Jersey’s vast Pine Barrens to hunt, gather wood, and collect berries. Socioeconomically, the Lenape were a relatively peaceful people who preferred amiable commerce over military conflict. They were also a matrilineal society that structured their communities around egalitarianism and democracy. Appropriately, each of their dispersed communities chose sachems, who served as representatives and advisors for their people. They held this esteemed position until they died or lost the respect of those they represented. [1]

The earliest known archaeological evidence of a Native American presence in the region can be traced back to an 8600 BCE Shawnee-Mineski site found near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The Lenape’s ancestors likely settled in the Lenapehoking region shortly thereafter, though the date of their ethnogenesis is debated. Archaeological surveys at Bartram’s Garden reveal that the site was likely used as a seasonal hunting and gathering ground by Native Americans, potentially Lenape, sometime between 3000 BCE and 1500 CE. Much of the site remains unsurveyed, however, so it is possible that there is more to be found that can add to its indigenous story.[2]

By the time Dutch and Swedish colonists began establishing settlements in Lenapehoking in the 1620s and 1630s, the Lenape’s population is estimated to have been between 8,000 and 12,000. This number is certainly lower than their pre-European contact population, as foreign diseases from earlier European traders and fishermen, such as smallpox and influenza, quickly wreaked havoc amongst Native American populations. As these viruses swept across the continent, historians estimate that most indigenous nations faced a casualty rate of between 75% and 90%. The Lenape’s population decline was likely also compounded by their roughly decade-long war with the Susquehannocks over control of trading rights with the Dutch at New Amsterdam.[3]

Despite their reduced numbers, the Lenape served as the dominant power in the region throughout most of the seventeenth century. Although they were generally welcoming to the waves of Dutch, Swedish, and Finnish settlers, granting them land and resources, they controlled where the colonists could settle and only authorized it in return for continued European trade goods. Conflict briefly arose in 1631, when investors under the Dutch West Indies Company attempted to start a large-scale plantation named Swanendael near present day Lewes, Delaware. The region’s Lenape, the Sickoneysincks, interpreted the plantation as a sign that the Dutch were transitioning their economic focus from trade to agriculture, a practice they found synonymous with the British colonial system’s pattern of exploitation and expansion. They subsequently raided the plantation, killing its thirty-two inhabitants. The scale of violence at Swanendael served as a precedent in the minds of early colonists of Lenape authority and the necessity of continuing a commerce-focused relationship.[4]

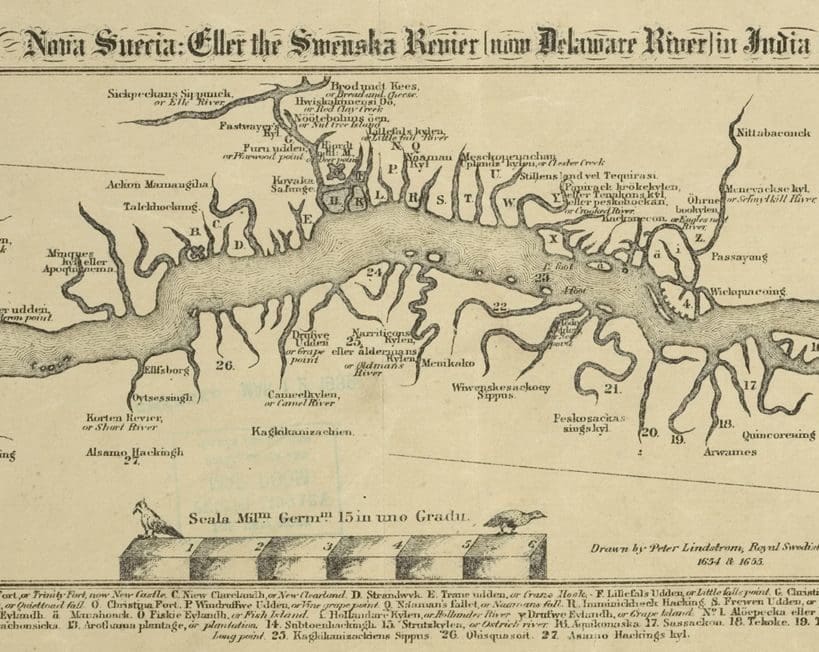

“Nova Suecia, eller the Swenska Revier [now Delaware River] in India Occidentalis,” map by Peter Mårtensson Lindeström, 1655 (Digital Public Library of America). The cropped map depicts the colony of New Sweden along the Delaware River. “Passayung” (Passyunk) can be seen on the right, while the Z is labeled as “Kinsessing”.

Many of the colony’s freedmen lived in Kingsessing, which today has maintained its name and a similar location along the southwest bank of the Schuylkill River. The settlement’s Swedish and Finnish colonists coexisted and traded with the Armewamese Lenape, who lived east of Kingsessing across the Schuylkill in Passyunk. Directly above Kingsessing was a roughly 1100-acre tract of land named “Aronameck,” very similar to the southern Unami word for “the greater stream.” Aronameck was settled by Peter Jochimson in 1648, and 102 acres of the property were eventually purchased by John Bartram in 1728. Today, this property is Bartram’s Garden.[5]

Detail: “A Map of the Improved Part of the Province of Penna. 1686-1687.” Thomas Holme and Francis Lamb. [Craig: “Kingsessing MS.”] Peter Yoccmb (Yocum) eventually subdivided his land; a portion of it later became Bartram’s Garden.

Featured Image: The Philadelphia City Planning Commission, Philadelphia Region When Known as Coaquannock Map, 1934. The map depicts the approximate location of believed Lenni Lenape settlements at the time of European arrival.

_________________________________

Notes

[1] Jean R. Soderlund, Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015): 6-24; Chief Quiet Thunder and Greg Vizzi. The Original People: The Ancient Culture and Wisdom of the Lenni-Lenape People. (Sweetwater: Nature’s Wisdom Press, 2020): 28-56.

[2] John L. Cotter, Daniel G. Roberts, and Michael Parrington, The Buried Past: An Archaeological History of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992): 11; “Phase II Archaeological Excavation at 36PH13 South Meadow Area of Historic Bartram’s Garden Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,” (March 2014) prepared by Matthew D. Harris, RPA, for the City of Philadelphia Division of Aviation, 8-24; “Historic American Landscapes Survey, John Bartram House and Garden (Bartram’s Garden), HALS No. PA-1, History Report,” MS report, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, HABS/HAER/HALS/CRGIS Division, Washington, DC, 9-18.

[3] Soderlund, Lenape Country, 17, 35, 44.

[4] Ibid, 35-48.

[5] Peter Stebbins Craig and Henry Wesley Yocum, “The Yocums of Aronameck in Philadelphia, 1648-1702,” National Genealogical Society Quarterly 71 (Dec. 1983).

[6] Soderlund, Lenape Country, 184-195.