Enclosing Bartram’s Garden

Bartram’s Garden is located in Lenapehoking, on the traditional land of the Lenape people. We are working to uncover and illuminate the complex and intertwining histories embedded in this land.

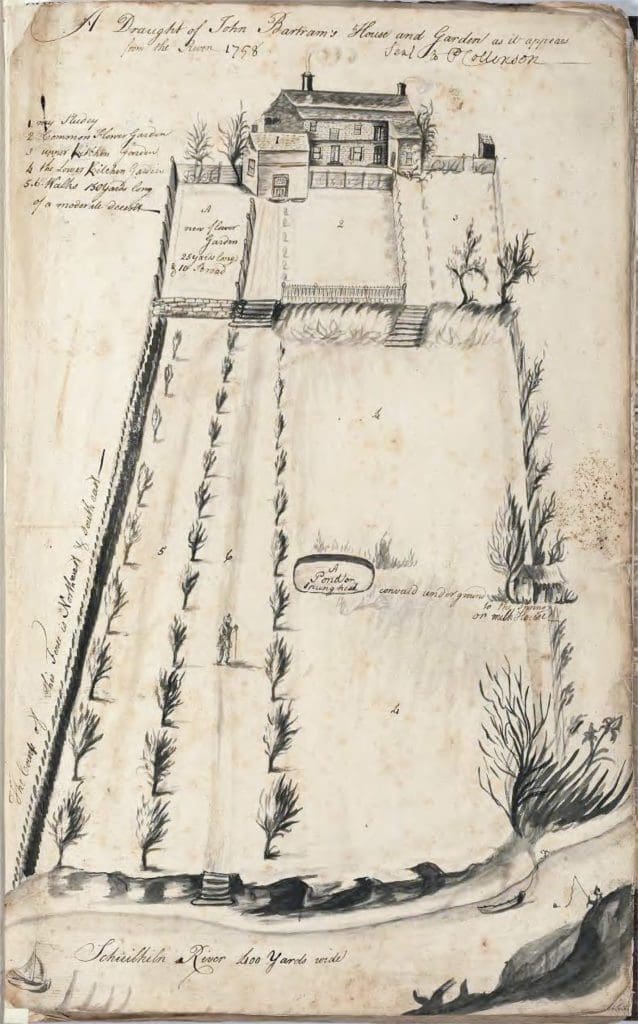

In 1758, William Bartram drew a picture of Bartram’s Garden. This drawing, which was sent to Peter Collinson in London, is one of the only known surviving images of Bartram’s Garden from the eighteenth century. By the time William produced his drawing, Bartram’s Garden was already enmeshed in the larger transatlantic network of exchange between England and its colonies in North America. In the 1730s, John Bartram, the founder of Bartram’s Garden and the father of William Bartram, began sending tree and shrub seeds across the Atlantic to his London correspondent and fellow botanist, Peter Collinson. Seeds from the garden were in high demand because, as Joel Fry points out, the early 1700s “saw a revolution in the gardens of England.” The seeds packaged and shipped by John Bartram “provided a fresh palette for these new landscapes, and Bartram’s early subscribers were soon joined by a register of the owners of important British gardens.”[1] Although the drawing does not feature all of the plants that John Bartram grew in his garden, it is significant both because of its unique status as a surviving object and also the fact that it gives historians and archeologists a rough idea of what the landscape of the garden may have looked like in the mid-eighteenth century. However, there is something else to William’s drawing, more subtle and unspoken, that makes clear that it was not just physical commodities that were transported back and forth between England and the garden – there were cultural ones too.

When William drew his picture, he was only 19 years old and not yet made famous by his mid-1770s Travels through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscogulges, or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws (Published in 1791). As the “best educated of his father’s children,” William attended the Philadelphia Academy from January 1752 to July 1755 where he “learned Latin and French and perhaps a little drawing.”[2] In fact, William often used his artistic skills to create drawings of the different flora that went along with the seeds his father was shipping across the Atlantic. William was never able to make himself a career through his artwork, but his drawings did help John Bartram establish Bartram’s Garden as a “center of botanic pursuits, recognized by an international community of artists, collectors, and natural historians as the source for so many of America’s newly discovered plants.”[3] Although more messy and less delicate than his later drawings – and marked with spelling errors that were corrected by Collinson – William’s portrait reveals a significant cultural phenomenon that swept England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and was transported to the colonies: the enclosure movement.

The enclosure movement was a process in England by which the government “granted landowners rights to improve previously uncultivated lands and enclose formerly common lands.”[4] Enclosure in England began after the 1660s, but it spread rapidly to the different colonies of the British Empire, especially North America. According to Patricia Seed, English colonizers laid claim to land in a distinct way: they constructed houses, gardens, and fences. Establishing a house was an important first step in this process because they carried much “cultural significance as registers of stability, historically carrying a significance of permanence missing even elsewhere in continental Europe.” However, houses were more than symbolic, as they “also established a legal right to the land upon which they were constructed. Erecting a fixed (not movable) dwelling place upon a territory, under English law created a virtually unassailable right to own the place.”[5] The fences and gardens that surrounded a house were also quite important as well.

English colonizers considered fences or hedges surrounding a house and the surrounding area to be markers of private property as these physical objects quite literally enclosed the land. The English labeled both fences and hedges as “improvements,” which had a culturally loaded meaning for the colonizers. According to Seed, the act of “improving” a piece of land “meant to claim it for one’s own agricultural or pastoral use by surrounding it with one of the characteristically English architectural symbols of the sixteenth century, the fence.”[6] In a similar fashion, the English also made sure to put the land to use, which often resulted in the planting of a garden. Much like the fence, gardens were extremely symbolic for the English. English gardens in the colonies were signs of possession that “represented the entire colonial ambition to possess the land by establishing a part of the project in a central and visible way.”[7] This was a distinct feature of the British Empire, as no other European power attached the same significance to gardens. As Seed puts it, “planting the garden was an act of taking possession of the New World for England. It was not a law that entitled Englishmen to possess the New World, it was an action which established their rights.”[8] As the English colonized more of the New World, the cultural values of the enclosure movement were transported from England to its colonies.

The land on which Bartram’s Garden is located is known as Lenapehoking, the traditional land of the Lenape people. The arrival of Dutch, Swedish, and English colonizers during the seventeenth century forced indigenous peoples from their lands.[9] By the time William drew the picture of Bartram’s Garden in 1758, the greater Philadelphia area had been controlled by the British Empire for almost a century. Although William went to school in Philadelphia and drew his father’s garden “as it appears from the River,” his drawing makes clear that he was aware of the physical and cultural meanings of the enclosure movement that flourished in England. As Zara Anishanslin points out, the enclosure movement occurred alongside a burgeoning print culture in Europe that “widely circulated maps and travel narratives describing landscapes and botanicals.”[10] In fact, William’s drawing is reminiscent of a now famous English papercut design by Anna Maria Garthwaite from 1707.[11] As an educated son of a wealthy Philadelphian Botanist, it should come as no surprise that William may have seen multiple portraits of landscapes and maps that pictured the values of the enclosure movement. It is worth divulging some of the subtle details of the image in order to flesh out these values so important to the British Empire.

To begin, William Bartram’s drawing of Bartram’s Garden is entirely enclosed. There is not a single broken line around the entire perimeter of the property. Where there is not a fence enclosing the garden, there is a natural barrier, such as a tree or shrub, and even the western bank of the Schuylkill River is heavily marked with ink and meets with the fencing around the property. William’s technique thus transforms the perimeter of the garden into a large rectangle that takes up most of the paper. Within this rectangle stand the different features of the garden, such as additional fences, trees, a pond, and, if you look close enough, John Bartram himself. He stands alone in his garden with a walking stick, although at first glance he blends with the trees along the walkway so as to not overpower the features of his garden. Additionally, with exception to the river, there is nothing pictured outside of these borders that mark the property of the garden. Instead, William used the area outside of the garden as a writing space where he titled his drawing and even created a small numbered key. By creating these borders, both natural and man-made, as well as including the lone figure of John Bartram, William showed “the principal symbol of not simply ownership, but specifically private ownership.”[12] With the enclosure movement in mind, William endowed the mundane borders of Bartram’s Garden with a unique cultural significance.

Also worth noting is how large the garden is in comparison to the rest of the features of the image. Although William took the time to add accurate details to his drawing of the Bartram House, it is almost dwarfed by the size of the garden – the lower garden itself takes up most of the page. In a similar fashion, the garden makes the Schuylkill River look like a creek despite being labeled 50 yards wider than the length of the walkways. Although he tried to make an accurate portrayal of the property with measurements, William purposefully prioritized the size of the garden and emphasized this space as significant. William drew the garden at the height of the enclosure movement (1750-1800), a time when gardens were important in both England and in the colonies, especially in Philadelphia. According to Therese O’Malley, “the practice of gardening was central to the idea of a new society in the colony of Pennsylvania,” and in Philadelphia “gardens were conspicuous as places of study and resort, and they were also status symbols.”[13] As mentioned above, William sent his drawing to Peter Collinson in London, and it’s possible this was an attempt to compare, imagine, and draw connections between Bartram’s Garden and Collinson’s own garden in London.

In a letter dated April 6, 1759, Collinson wrote to John Bartram about William’s drawing. He proclaimed that, “We are all much Entertained with thy draught of thy House and Garden the situation most delightful and that for our plants is well chosen I shall endeavour to furnish it.”[14] Collinson often sent various plants back to Bartram’s Garden, so according to his letter it seems as though he was trying to imagine where his plants might go inside of Bartram’s enclosed garden space once they traveled across the Atlantic. Collinson was probably “much Entertained” with the size of the garden, its enclosed spaces, and maybe even the available open space in the “new flower Garden 25 yards long & 10 Broad.”[15] William’s drawing pictured a respectable garden, one that could compete with the lavish gardens in London and invited the possibility of improvement.

William Bartram’s A Draught of John Bartram’s House and Garden as it appears from the River has been reproduced in a number of articles and books on garden history and histories of Bartram’s Garden. As one of the only surviving images of John Bartram’s house and garden from the eighteenth century, William’s drawing deserves the attention and recognition it receives. Unfortunately, most scholars have not analyzed this image beyond its status as an important material object. As I have shown here, William’s drawing contains unspoken cultural symbols that were long part of the British imperial project. Neither Peter Collinson, John Bartram, nor William Bartram ever mentioned the straight, connected lines that form the perimeter of the property. They also never commented on how the assortment of the house, garden, and fence were brought together in a classic representation of the enclosure movement. Yet, as with many cultural phenomena, they could leave these details unspoken, only ever understood by those who knew what it meant to enclose a garden.

Notes

[1] Joel T. Fry “America’s “Ancient Garden:” The Bartram Botanic Garden, 1728-1850,” Knowing Nature: Art and Science in Philadelphia, 1740-1840, ed. Amy R.W. Meyers (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011), 65.

[2] Ibid., 72.

[3] Therese O’Malley, “Cultivated Lives, Cultivated Spaces: The Scientific Garden in Philadelphia, 1740-1840,” Knowing Nature: Art and Science in Philadelphia, 1740-1840, ed. Amy R.W. Meyers (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011), 43.

[4] Zara Anishanslin, Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the British Atlantic World (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2016), 47.

[5] Patricia Seed, “Houses, Gardens, and Fences: Signs of English Possession in the New World,” Ceremonies of Possession in Europe’s Conquest of the New World, 1492-1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 18.

[6] Ibid., 25.

[7] Ibid., 29.

[8] Ibid., 30.

[9] Jean R. Soderlund, “Colonial Era,” The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/colonial-philadelphia/.

[10] Zara Anishanslin, Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the British Atlantic World (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2016), 47.

[11] Anna Maria Garthwaite was a female silk designer in Spitalfields, London during the 1730s-1750s. Garthwaite, much like Collinson and Bartram, was a part of the same transatlantic trade network between England and North America. Many of her silk designs were inspired by plants and drawings of plants that were sent over from the colonies to London, such as the very ones sent from Bartram’s Garden to Peter Collinson. For more on her life as a silk designer, see Zara Anishanslin, “Part One: ‘Our Incomparable Countrywoman:’ Anna Maria Garthwaite, Silk Designer,” Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the British Atlantic World (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2016), 25-103.

[12] Patricia Seed, “Houses, Gardens, and Fences: Signs of English Possession in the New World,” Ceremonies of Possession in Europe’s Conquest of the New World, 1492-1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 20.

[13] Therese O’Malley, “Cultivated Lives, Cultivated Spaces: The Scientific Garden in Philadelphia, 1740-1840,” Knowing Nature: Art and Science in Philadelphia, 1740-1840, ed. Amy R.W. Meyers (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011), 51.

[14] Peter Collinson letter to John Bartram, April 6, 1759, in The Correspondence of John Bartram, 1734-1777, edited by Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkely (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1992) 463.

[15] William Bartram, A Draught of John Bartram’s House and Garden as it appears from the River, 1758.