George Bartram (1767-1840)

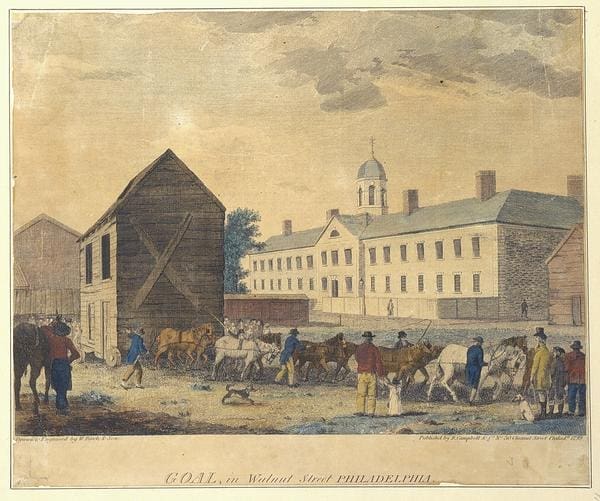

(Image: “Goal, in Walnut Street Philadelphia [graphic] / Drawn & engraved by W. Birch & Son.” Philadelphia: Published by R. Campbell & Co. No 30 Chesnut [sic] Street, 1799. Courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia)

The following is an excerpt from “Those We Met Along the Way,” a series of vignettes recounting the African American community’s development in Kingsessing, Slavery, and the Bartram Family.

*The Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons was established in 1787 by Dr. Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Franklin, and other prominent Philadelphia figures.

*Walnut Street Jail began using solitary confinement to punish prisoners in the 1790s.

*The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 empowered magistrates and judges to grant certificates to enslavers, their attorneys, and agents to take enslaved people across state lines.

Born in 1767, George Bartram, the grandson of John Bartram, wore quite a few hats throughout his life.[1] After graduating from the University of Pennsylvania in 1783, Bartram took on roles as an alderman, prison inspector, and President of Select Council. In addition to his work as a public servant, Bartram collected orders in the city for Bartram’s Garden.[2]

As an inspector of Philadelphia prisons, Bartram and a committee of twelve men visited and inspected the prison and prisoners’ conditions. The committee presided over prisoner pardons, visitation requests, and punishments and ensured prisoners were fed, clothed, and treated adequately. Home to the Walnut Street Jail, Pennsylvania set the standard for the carceral state following the American Revolution. The first of its kind, the Walnut Street Jail was a penitentiary and a jail and replaced public punishments with solitary confinement. George Bartram served as a prison inspector from 1804 to 1813.[3]

During Bartram’s tenure as an inspector, the Black inmate population convicted in Philadelphia courts sentenced to Walnut Street Jail increased 113.8%.[4] This increase coincided with a 52.9% increase in the Black population of Philadelphia between 1800 and 1810.[5] Established in 1787, The Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons made significant strides to improve Philadelphia prisons’ conditions. One major improvement was the separation of inmates by gender. Before the Society’s efforts to establish separate correctional facilities, men, women, and children were confined to one large living space.[6]

After acting as a prison inspector, George Bartram became an alderman in Philadelphia. One of his first acts as alderman was to oversee the indenture servitude contract of 14-year-old Augustus Stephenson. In November 1814, Stephenson was indentured as a waiter to Francis Duffee for seven years. Augustus Stephenson and his father signed the agreement. However, in December 1815, Duffee brought Stephenson before George Bartram again and, with the minor’s consent, sold the contract to Samuel Vanlear. Stephenson’s father sued to have his son released from Vanlear, arguing that the indentured contract between the pair was illegal because his son was unable to consent to legal transactions as a minor. He also noted that the original contract bound his son to Duffee as labor but did not grant guardianship over the boy, meaning Duffee had no authority to broker a new contract for Stephenson.[7]

In addition to the claims of Stephenson’s father, lower courts argued that George Bartram had no authority to oversee indentured contracts as an alderman, a task usually reserved for a justice of the peace. The case rose to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which determined that the indenture was invalid. The court found that indentured servitude contracts fell under Bartram’s jurisdiction because “alderman have the same powers in relation to this subject, that belong to justices of the peace.”[8] However, the courts deemed the assignment void because the father had not consented to an indentured contract with Samuel Vanlear. Augustus Stephenson’s consent was not sufficient for approving a new agreement. In the court’s ruling, Chief Justice William Tilghman added that “it has lately become a lucrative business to have a boy bound for the purpose of selling him, and if his consent alone is sufficient, it may be obtained by a trifling bribe perhaps, or if he be of tender years, by intimidation.”[9] Although there was no evidence that Augustus Stephenson was coerced into the sale of his indentured contract, the original contract is proof that Bartram knew the boy had a parent/guardian and failed to gain the father’s consent. The contract of Augustus Stephenson was not Bartram’s last questionable indenture.

In 1820, a newly manumitted woman from Accomack County, Virginia, arrived in Philadelphia seeking employment opportunities, where she met Isaiah Knight.[10] Knight “kept an intelligence office” and offered to help the woman find a work placement for 25 cents. While he searched for job placement, he provided her with room and board free of charge. After nearly ten days, Knight claimed that he found her a job that included housing but, she needed to go before a magistrate to sign articles of agreement. In George Bartram’s office, they met with John Huffnagle, a local hardware store owner. She made her mark on the pre-prepared contracts and went home with Huffnagle. After being in the storekeeper’s employ for a while, she asked for her wages and permission to visit friends; both requests were denied. Huffnagle claimed that she was an indentured servant for five years, and he had paid Isaiah Knight $150 for her contract. After several months and assistance from her former enslaver, Huffnagle discharged the woman.[11] Knight probably gained the unnamed woman’s trust with the kindness he showed her when she first arrived in the city. He was her first friend, and she had little reason to believe that he was selling her freedom.

For George Bartram’s part in the ordeal, the prepared documents indicate that the three men came to an understanding before bringing the woman to his office. Under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, Knight only had to claim to be her owner and present “proof to the satisfaction of such judge or magistrate, either by oral testimony or affidavit taken before and certified by a magistrate.”[12] Free Black people in Philadelphia and other parts of the country were easy prey for Isaiah Knight. The broad language of the legislation left them vulnerable while protecting the property rights of enslavers.

George Bartram died in 1840, at the age of 73.[13]

Notes

[1] George Bartram was the son of Ann Bartram, youngest daughter of John Bartram. The National Gazette (Philadelphia, PA), February 17, 1824.

[2] The National Gazette (Philadelphia, PA), March 24, 1828.

[3] Annual Report of the Inspectors of the Inspectors of the Philadelphia County Prison, Made to the Legislature, Volume 8, Parts 1855-1866. JMG Lescure, 1855. Bartram did not serve as a prison inspector in 1811.

[4] Leslie Patrick-Stamp, “Numbers That Are Not New: African Americans in the Country’s First Prison, 1790-1835.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 119, no. 1/2 (1995): 95-128. Accessed February 9, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/20092927.

[5] Ibid, 110.

[6] Norman Johnston, “Prison Reform in Pennsylvania”, https://www.prisonsociety.org/history

[7] Thomas Sergeant, Reports of Cases Adjudged in the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, Volume 1 (Philadelphia, PA; Philip H. Nicklin, 1818), 248.

[8] Ibid, 248.

[9] Ibid, 250.

[10] The formerly enslaved woman is never mentioned by name, however, she was enslaved by and later manumitted by a family with the surname Stokely. See: Daniel Meaders, Kidnappers in Philadelphia: Isaac Hopper’s Tales of Oppression, 1780-1843 (Routledge, 2019), “The Fraudulent Indenture”, N.A.S., May 27, 1842, 202.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Proceedings and Debates of the House of Representatives of the United States at the Second Session of the Second Congress, Begun at the City of Philadelphia, November 5, 1792., “Annals of Congress, 2nd Congress, 2nd Session (November 5, 1792 to March 2, 1793), 1415.

[13] Robert Burns Beath, An Historical Catalogue of the St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia with Biographical Sketches of Deceased Members, 1749-1913, Volume 1, (St. Andrew’s Society of Philadelphia, 1907), 108.

Related Reading

Anderson, Annie. “Prisons and Jails.” Accessed February 9, 2020. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/prisons-and-jails/.

Galenson, David W. “The Rise and Fall of Indentured Servitude in the Americans: An Economic Analysis.” The Journal of Economic History 44, no. 1 (1984): 1-26. Accessed February 11, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/2120553.

Manion, Jen. Liberty’s Prisoners: Carceral Culture in Early America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

Patrick-Stamp, Leslie. “Numbers That Are Not New: African Americans in the Country’s First Prison, 1790-1835.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 119, no. 1/2 (1995): 95-128. Accessed February 9, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/20092927.

Teeters, Negley K. The Cradle of the Penitentiary: The Walnut Street Jail at Philadelphia, 1773-1835. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Prison Society, 1955.

Wilson, Carol. Freedom at Risk the Kidnapping of Free Blacks in America, 1780-1865. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2015.