Periodical Cicadas (not) in the Garden

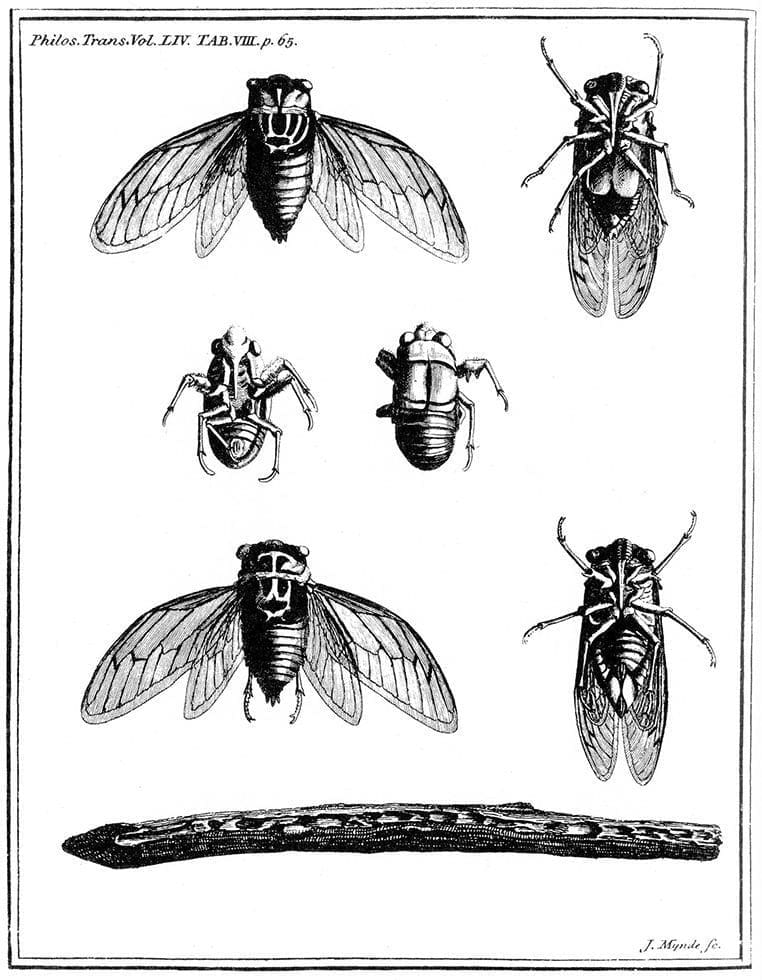

Over the last several weeks, millions of Brood X (also known as the Great Eastern Brood) periodical cicadas have emerged from northern US soil, a place that they have called home since 2004. These periodical cicadas have spent the last 17 years living below the surface of the earth, only to emerge for a few weeks in the late spring/early summer of this year before they mate and die shortly thereafter. Once the soil reaches the correct temperature (approximately 64°F), the cicadas crawl their way out of the ground, often leaving behind small mounds of mud with an opening no larger than a penny.[1] After their emergence, the cicadas attach themselves to various flora, which could include anything from tree trunks to blades of grass. Following a short amount of time, the insects shed their shell, leaving behind fields of empty brown husks or chrysalises. The cicadas emerge from their shells a bright white, but they are unable to fly just yet. Once the body of the insect hardens, it turns into a vibrant orange and brown, almost reminiscent of the beloved fall holiday to come four to five months later, and then the cicadas take flight to look for a mate. During this time, the cicadas produce their famous (or infamous) song, a loud and piercing buzz that can reach up to 100 decibels![2] Once the insects mate, the female cicadas typically bury their eggs into the branches of the surrounding trees, and can lay up to 600 eggs. In about six to ten weeks the eggs hatch; meanwhile, the adult cicadas die off, often leaving mounds of insect carcasses at the bases of trees. The cicada nymphs then drop from the tree branches, burrow into the ground, and will not emerge for another 17 years, thus starting the life cycle all over again.

If you have been paying attention to the news lately, these insects have been making headlines. In Cincinnati, a stray cicada caused a motorist to crash their car earlier this month. They have even left an impact on the political scene, as a swarm of cicadas delayed a press corps plane headed for Europe, and one cicada even landed on Joe Biden before he left for his first overseas trip as president. Yet, if you live in the greater Philadelphia area, you may be wondering, where are all of the cicadas? According to one article in The Philadelphia Inquirer, whether one of America’s oldest cities would experience this natural curiosity has been a big question mark. As this sweltering June carries on, it has started to look like the city’s residents will miss out on this occurrence. But why? According to Jon Gelhaus, curator of Entomology at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University and professor of Biodiversity, Earth and Environmental Sciences, others have been wondering the same thing. In a blog he posted at the end of April, Gelhaus expressed disbelief at a map produced by the University of Connecticut that shows areas where the 17 year periodical cicada have been spotted this year – Philadelphia is bare. He rightfully asks “what does it mean?” Gelhaus concludes that it could not be a sampling issue, nor that it’s an issue of the city, as the cicadas have previously swarmed the Baltimore and D.C. areas in the past. Gelhaus took to the historical record to see if he could find any trace of these cicadas in the Philadelphia area, and one of the places he points to is Bartram’s Garden.

According to Gene Kritsky, the earliest documentation of the periodical cicada in Philadelphia was in 1715 by the Reverend Andreas Sandel. Over the next century, multiple contemporaries commented on or read about the appearance of the periodical cicadas, including the Swedish traveler Pehr Kalm in 1756, the botanist Carl Linnaeus, who named the periodical cicadas Cicada septendecim in 1758, the London based botanist Peter Collinson, and even John Bartram’s son, Moses Bartram, wrote a letter describing the life cycle of cicadas.[3] John Bartram (1699-1777), the founder of Bartram’s Garden, recorded in a letter to Peter Collinson dated April 26, 1737 (five years after the appearance of the 1732 cicadas) the unusual presence of “the periodical appearance of a particular species of Locust, I have remarked twice in my memory with us in Pensilvania that every fifteenth year they are seen in prodigious Swarms.”[4] Collinson showed much interest in Bartram’s mention of the cicadas and his enthusiasm encouraged Bartram to take more detailed notes the next time they appeared, that being 1749.

During the late spring of 1749, John Bartram recorded the life cycle of the periodical cicadas and sent his findings to Collinson:

May the 10th: 1749 Early in the Morning was observed they had Quitted their Earthly aboads, at first they are all over White, except their Eyes, which are Red, in a few Hours the Air Changes them, into a Dark Brown, like the Specimen they continued coming out Innumerable, to the 15th: the Grass, bushes & Trees &c are covered with them When they are a Day or Two old, the Males begin to Sing, which is performed by a Tremoulous Motion of Two bladers, by the air under their Wings, and now there is a Continued Din (So great as to Interrupt Conversation) all over our Woods, & Orchards, flying too & fro Seeking the Females…

Bartram continued on describing the way in which the female cicadas “Dart” tree branches after mating with the male cicadas:

It is surprising with what dexterity & quickness they work through the Toughest Bark… at the same time that they Penetrate the wood, they lay an Egg from Twelve to Eighteen Close together… and thus they proceed on darting the Twiggs until their stock of Eggs is exhausted, In this work they Continued until the 8th of June & then there was scarcely one to be seen, the greatest part of them become the prey of most four- footed animals… those that survive these depradations, being spent with their several functions, pine away & die.[5]

Other than the timing for when the cicadas emerge, Bartram’s observations on the behaviours of the adult periodical cicadas were quite accurate. According to Kritsky, Peter Collinson went on to use Bartram’s descriptions in a paper that he read to the Royal Society of London in 1763.[6] However, Collinson was not the last contemporary of John Bartram to write about the periodical cicadas. Seventeen years after the 1749 emergence, Bartram’s son, Moses Bartram, published his observations of the cicadas in the 1766 edition of the Gentleman’s Magazine.

In his piece, Moses Bartram gave a description of the periodical cicadas that was similar to his father’s notes from 17 years prior, although he seemed to be more bewildered by the nature of the life cycle of the insects:

How astonishing therefore and inscrutable is the design of providence in the production of this insect, that is brought into life, according to our apprehension, only to sink into the depths of the earth, there to remain in darkness, till the appointed time comes when it ascends again into the light by a wonderful resurrection![7]

Moses Bartram also included more descriptions about the many different perils that a cicada could face during its life cycle, and emphasized that these insects could perish at any given moment. Moses’s observation still has some merit to this day, as the periodical cicadas “do not possess special defensive mechanisms — they do not sting or bite.”[8] Because of this, the insects often fall victim to various kinds of animals, something Moses noted toward the end of his paper, “In the very egg, it is the prey of ants and birds of every kind; in that of grub, by hogs, dogs, and all carnivorous animals that can unearth it; and in its most perfect state, not only many kinds of beasts and birds, but even men, many of the Indians, it is said, feeding sumptuously upon them.”[9]

Thanks to the records of John and Moses Bartram, we know that the periodical cicadas have a history in Philadelphia and Bartram’s Garden. If you were looking forward to studying these same periodical cicadas as John and Moses Bartram did in the mid-eighteenth century, however, you may have to look somewhere else. In April, Jon Gelhaus optimistically pointed to West Philadelphia and Bartram’s Garden as possible locations to see these incredible insects. Nevertheless, if you have recently taken a stroll through the garden during this warm June, it’s likely that you did not see the Brood X periodical cicadas. No overwhelming buzz or apocalypse-like flash of insects, not even a trace of small mud tunnels. The Brood X cicadas are estimated to die off at the end of June and beginning of July, not to emerge again until 2038. In Philadelphia, however, it appears that the question is not when the cicadas will return, it’s if they will ever return at all.

Notes

[1] John Cooley, “General Periodical Cicada Information,” Cicadas, February 16, 2017, https://cicadas.uconn.edu/.

[2] Biordi Gaby, “Keep Calm and Cicada On: Brood X Is Coming!” Cincinnati Zoo Blog, April 20, 2021, http://blog.cincinnatizoo.org/2021/04/20/keep-calm-and-cicada-on-brood-x-is-coming/?fbclid=IwAR0e40VE19vXQX-kRWO1gRqaAzJs9aZn0IoFKOalGO-CC9X3YFVoygdkqT0.

[3] Gene Kritsky, “John Bartram and the Periodical Cicadas: A Case Study,” in America’s Curious Botanist: A Tercentennial Reappraisal of John Bartram, 1699-1777, edited by Nancy E. Hoffmann and John C. Van Horne (Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 2004), 43.

[4] John Bartram to Peter Collinson, April 26, 1737, quoted in Gene Kritsky, “John Bartram and the Periodical Cicadas: A Case Study,” 44.

[5] John Bartram to Peter Collinson, undated, quoted in Gene Kritsky, “John Bartram and the Periodical Cicadas: A Case Study,” 47.

[6] Gene Kritsky, “John Bartram and the Periodical Cicadas: A Case Study,” 48-49.

[7] Moses Bartram, “Observations on the Cicada, or Locust of America, which appears periodically once in 16 or 17 Years,” The Gentleman’s Magazine (London, 1766), 391.

[8] John Cooley, “General Periodical Cicada Information,” Cicadas, February 16, 2017, https://cicadas.uconn.edu/.

[9] Moses Bartram, “Observations on the Cicada, or Locust of America, which appears periodically once in 16 or 17 Years,” The Gentleman’s Magazine (London, 1766), 392.