Juneteenth: Freedom and Black Southwest

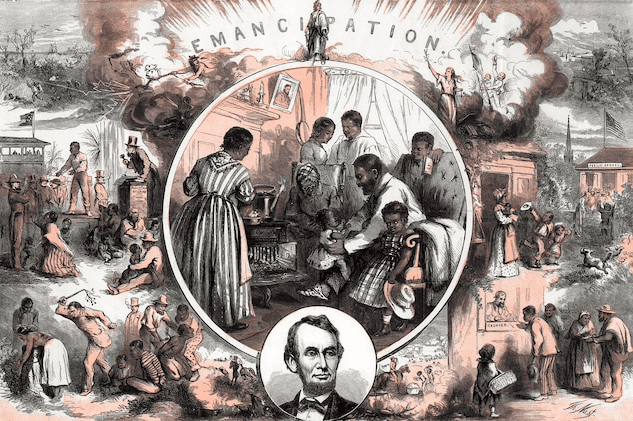

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation (effective January 1, 1863), which stated that all enslaved people in Confederate states were free. However, enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, did not learn of their freedom until June 19, 1865, when Union Army General Gordon Grander arrived to announce the Civil War had ended. Juneteenth (June and nineteenth) is a holiday that celebrates freedom and a day of remembrance for enslaved men, women, and children in America. Through song, food, and other means of expressing culture, Black people have observed Juneteenth since 1866.

With Juneteenth in mind, looking at the history of Black people in Southwest Philadelphia reveals stories of freedom and emancipation. But, they are also stories of hardship and struggle. After the passing of the Gradual Abolition Act of 1780, the Black community in Pennsylvania grew rapidly.[1] As children born to enslaved women inherited their legal status, the law ensured freedom for future generations. Many free Black people, formerly enslaved, and individuals fleeing slavery made their home in Philadelphia, particularly southwest.

As early as 1790, a free Black person lived at Bartram’s Garden, where federal census records show one “free persons all other.” Later documents, up to 1850, show a growing number of free individuals on the property.[2] Because they were not listed as a head of household, little is known about them, and further research is required to identify them. However, the African American Census of Philadelphia provides details into the lives of their neighbors. By 1847, 97 of the 156 Black residents that lived on Oak Street (present-day Ludlow Street) were Pennsylvania natives. The remaining 59 individuals represent one of the earlier migrations of Black people seeking a new life in the North. The 59 residents of Oak Street that migrated consisted of 19 people born enslaved. While 14 of them were manumitted, 5 of them purchased their freedom.[3] Some of the entries for formerly enslaved Oak Street residents provide valuable information for understanding their lives before liberty.

Like other families in their neighborhood, Adeline Kelley and Amy Wood made ends meet by sharing a home on Oak Street. Both were manumitted in Virginia and migrated to Philadelphia. Amy Wood was born enslaved and emancipated by Lucy Wood (1743-1826), sister of Patrick Henry, who famously proclaimed, “give me liberty or give me death!” in favor of the American Revolution.[4] In the years leading up to her death, Lucy Wood lived in Albemarle County, Virginia, and her son, John Wood, handled her financial affairs.[5] Wood’s poor finances forced her son to request loans from relatives. Lucy Wood was distantly related to First Lady Dolley Madison.[6] In a letter dated December 22, 1820, John wrote former President James Madison to borrow $200 to $500 on his mother’s behalf to avoid selling a slave. According to John’s letter, “the small pecuniary aid I am about to ask, would be most willingly afforded by my mother cou’d [sic] it be done without the Sale of a negro to which she is extremely averse…”[7] None of the documents mention the circumstances of Amy Wood’s manumission. Wood was listed as head of household for a family of five. There were three children between the ages of 6 and 16, and two attended the Oak Street School. They were listed as 5 of 9 occupants in the home.

Adaline Kelley was born enslaved and manumitted by Ann Thomas Bedford of Richmond, Virginia. Kelley raised her three children, two sons and a daughter, alone as her husband remained enslaved in Virginia. Kelley earned $1.50 each week as a domestic worker taking in laundry. In addition, two of her children worked at the tobacco mill for $1 each per week. Combining their wages brought the household income to $14 monthly. Although, in today’s terms, the family combined for a monthly income of $438.74, none of the children attended school.[8]

Over on Darby Road (now Woodland Avenue), Agnes Hill raised five children on her own. While her husband remained enslaved in Virginia, Hill worked as a washerwoman, earning $2 per week. Three of her children attended the Oak Street School, and two children were indentured servants. By indenturing two of her children outside the home, Hill ensured that they were provided for and taught a trade. As a way of circumventing poverty, some parents chose to sign children into indentured servant contracts. The archival record does not explain how Hill chose which of her five children to send to work outside the home. Hill’s family shared a home with another family resulting in 8 people sharing two rooms.[9]

In the wake of recent issues related to racial injustice, Pennsylvania and forty-six other states will observe Juneteenth. As we celebrate the freedom of those that endured slavery, we must also praise them for surviving. The holiday is an opportunity to honor those that came before us and lament their experiences. It is also a chance to reflect on the way historical events inform the present. The ripple effect of slavery has had a long-reaching impact on the lives of Black people. In the future, maybe Juneteenth will be observed in every state across the country.

Notes

[1] No enslaved people were freed at the passing of the 1780 law. Children born to women enslaved in 1780 were indentured to their mothers’ masters until the age of 28.

[2] Year: 1790; Census Place: Kingsessing Town, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Series: M637; Roll: 9; Page: 277; Image: 557; Family History Library Film: 056814

[3] African American Census of Philadelphia. Swarthmore, Pennsylvania: Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College.

[4] Thomas S. Kidd, Patrick Henry: First Among Patriots (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2011), 99. – – African American Census of Philadelphia. Swarthmore, Pennsylvania: Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College.

[5] “To James Madison from John H. Wood, 22 December 1820,” The Papers of James Madison, Retirement Series, vol. 2, 1 February 1820-26 February 1823, edited by David B. Mattern, JC Stagg, Mary Parke Johnson, and Anne Mandeville Colony (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013), 182-183.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] African American Census of Philadelphia. Swarthmore, Pennsylvania: Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College. – – Monthly income calculated using officialdata.org to account for inflation.

[9] As of 2014, $2 per week equates to $217.95 per month. – – Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, African American Census, 1847 Swarthmore, Pennsylvania: Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College.

(Image Artist Thomas Nast created illustrations depicting formerly enslaved people following the end of the Civil War. National Geographic, 2019)