“There’s Nothing a Child Cannot Learn”: New Connections with Patterson Elementary School & Bartram’s Garden

A conversation about learning with Leslie Gale, School Education Manager at Bartram’s Garden, and Beverly Ritter, first-grade English Language Arts teacher at John M. Patterson School.

This interview originally appeared in the September 2023 edition of the Southwest Globe Times newspaper.

Would you each introduce yourselves?

Leslie Gale (left), School Education Manager at Bartram’s Garden, and Beverly Ritter, first-grade English Language Arts teacher at John M. Patterson School.

Leslie Gale (LG): Everybody under the age of 15 who comes to Bartram’s Garden knows me as Mrs. Leslie, or occasionally “the lady with the strange seedpods” or “the lady who will show us where the snakes live in the winter.” I’ve been working here at Bartram’s Garden for 17 years. I’ve been an outdoor educator for 19 years, and before that I was a classroom teacher.

Beverly Ritter (BR): I am a first-grade ELA [English Language Arts] teacher at Patterson Elementary. Go Patterson Bears! My students know me as Ms. Ritter. I’ve been at Patterson for 12 years, teaching first grade, and this year I’m very excited because I will transition to becoming the full-time literacy teacher. My co-worker and I will co-teach: Mr. Console will teach math, I will teach literacy. We’re very excited to begin this new school year. And I just found out that Mrs. Leslie is “the dissecting woman”!

LG: That’s my superhero name! “Let’s open up this plant and find where those seeds began!” Also, I want kids to know that nature doesn’t just exist in a park like Bartram’s Garden—[you] can nurture and see and encourage nature on your block, in your school yard. I also never want them to think this is just a place they go for school: I want them to know it’s a park, they can bring their families, they can just come for fun!

Tell us about this new partnership between the Garden and schools like Patterson.

LG: Bartram’s Garden is working closely with Southwest public schools like Patterson Elementary: students come to the Garden 2–3 times per month, and Teacher Marion and I are going into the classrooms 2–3 times a month, so kids are seeing us a lot more. The curriculum parallels what the teachers are doing so that we’re supporting what they’re doing in the classrooms—so if Ms. Ritter’s class is learning habitats, we can look at different habitats: “Let’s look at the pond! What’s different about the pond?” and help develop that vocabulary around noticing, observing, and asking questions. The teachers set the curriculum and it’s beautiful, so we’re supplementing it so that kids are getting these authentic outdoors, in-nature experiences that are enriching what they’re learning, enriching their language development, enriching their physical development.

BR: We started [this partnership] last year, and . . . it’s great because in fourth grade at Patterson, the students have a collaboration with John Heinz [National Wildlife Refuge]. This is getting them used to and exposed to nature, learning the vocabulary, learning how to take care of the environment, what are the native wildlife that live here.

LG: The third grade did a unit on weather, so we did a whole day about clouds, and we talked about evaporation, precipitation, and even climate change. The kids and I started talking about “Where’s the snow?” We drew the different kinds of clouds in white crayon on black paper so that they could identify different kinds of clouds and notice, “That one’s a fair-weather cloud, but ooh, that one’s going to make rain.” I could talk about weather for hours!

BR: I want to do that lesson!

LG: Last year I started out [teaching] navigation across the board. [The first-graders could] do pop quizzes: Which direction is east? Where’s west?

BR: [We want] them to learn to navigate the grounds. We purchased compasses for them! In the classroom we started talking about directions, and we learned how to read the compass and navigate to different areas in the school building. The students navigated until they could find a treasure box with a classroom prize, like 10 minutes of extra recess. The students were working with partners and taking turns trying to read the compass.

So the students are also learning to work together.

BR: Coming [to Bartram’s Garden] helps the students learn to regulate themselves, have patience, be able to cooperate—all those things are helping them make connections in the brain!

LG: It’s also interpersonal! Being able to navigate walking through the grounds and understanding where your body ends and the next person begins [so you don’t bump into your friend]. How do we share information quietly? How do we move together? Beverly and I were talking a couple weeks ago, and I have realized I want to do more stories—both going into the classroom and reading stories, and doing shared writing. I trained as a reading recovery teacher and I see how important that reading, storytelling, and writing all is to developing somebody who is a thinker and an explorer.

And developing empathy!

LG: Yes, and not just with other people but with other organisms: the land, the animals, the plants.

BR: Mrs. Leslie does a wonderful job at bringing that out in the students when we’re reading and writing. She’s excellent at explaining what we’re doing, she’s very thorough. And the students get excited! They love to see her!

LG: In my ideal, I’m partners with the kids. When we were walking through the Garden, I noticed that the sound of the conversation changed as we were walking down a winding path: it affects them like magic. The attention is less about messing with a buddy and more about “What’s that bird I’m hearing? What’s in the ground?”

BR: [They’re] building curiosity.

LG: And the questions they come up with are so amazing and sophisticated! And that’s part of giving kids the vocabulary—they have the ideas, they have the questions. But [we’re] giving them the language so they . . . have the words to describe it.

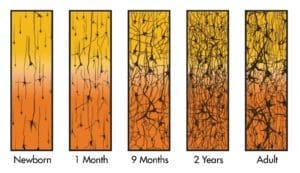

BR: May I show you something? This is why it is so important to expose children to as much as possible when they’re in their early childhood years. This is a picture showing the neuron [connections] in a child’s brain. Those connections are made and become stronger every time new information is taken in. When children are around 7, the end of early childhood, those connections that are not strong start to fall off. . . . What’s left is the foundation for learning for the rest of their lives, so we want them to have as strong a foundation as possible.

Ms. Ritter shared this diagram showing how neuron connections, known as synapses, get stronger and more numerous during early childhood, but only the strongest connections are retained in adulthood. Source: JL Corel, The postnatal development of the human cerebral cortex (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 1975.

How can we help children build those connections for learning?

BR: Children learn through play. We may think that they’re just running around in circles, but they’re learning about balance, about the vestibular system, about their relationship to the planet and gravity: when children are playing, they are making new connections, and they [need to] use all their senses to do that. With traditional education, just sitting in a classroom and listening to a lecture and looking at a book or a smartboard, that doesn’t make very strong connections [in the brain].

LG: [The navigation lesson] was about place. Where am I in this place? Understanding how big places are or how big the planet is––that’s hard to wrap your mind around when you’re 6! It’s hard to understand how far away things are, or how close they are. I always ask kids to draw a map of their own neighborhood—it’s about awareness, observation.

BR: For example, our class was learning about animal habitats in school and Leslie suggested, “Let’s do [that lesson] at the Garden!” We started in the classroom reading stories about animal homes and we talked about which kinds of animals might live in burrows. Then here at the Garden, one of the students, Sam, actually found a burrow by a tree!

LG: And then we started using our observation skills and asking more questions. We were noticing the aerial burrows, like in a tree where the squirrels or woodpeckers live, and the kids were the ones asking, “What lives in here? What are they doing? Where do they get their food?” and continuing on. And making all these connections and having these varied experiences—it all goes back to language acquisition!

BR: And just building more connections in the brain. If you think of a fireworks show on the Fourth of July, at the beginning you have little fireworks, and that’s a student who might not have had many experiences in their life. But the finale, [with lots of different fireworks], that’s a student who has been read to, who has [visited different places], who has touched things, who smells things, who tastes things.

LG: It’s about brain development, it’s about language acquisition, and it’s simply about richness of life. The more we experience, the richer our lives are, especially when we’re learning with all of our senses. [And kids] learn so much through movement. That’s what they’re learning from running around in circles! Being alive in a physical world is very complicated—why shouldn’t we be exposing kids to how complicated and fabulous it is? It’s one of the reasons I love teaching decomposition—because there is a cycle: “These dead plants are breaking down—where are they going to go? Where are they going into the soil?”

BR: There’s nothing that a child cannot learn if we break it down for them.

What are you excited about this year for your classroom?

LG: For the past two years, I’ve been trying to think of ways to talk more explicitly about the climate crisis. And I did it this summer with one of my lessons, where we design our own version of the city [and] I will introduce new variables for kids to design their cities around. I’m very excited to design that lesson and test it with the Patterson children.

BR: I want to do that! For my classroom, not only will the students be visiting the Garden regularly, but we are also taking field trips throughout the city to different places to get them out of the classroom: the Academy of Natural Sciences, the Franklin Institute, Lankenau [Hospital Education Center], the Swedish Museum, the aquarium—just trying to expose them to as much as possible to help reinforce what they’re learning inside of the classroom and taking it outside to apply it and make connections. Experiences and connections—those are my two words!

How did you two first get connected?

LG: Karen McKenzie and Tammy Cantagallo were the first two teachers I really got to know from Patterson, [then I met Beverly through field trips.] I love Beverly’s classroom style. Every once in a while I meet a teacher who makes me think, “Oh I should have stayed in the classroom”—she’s one of them. We started talking, and she said she wanted [to create] the outdoor education experience that her kids had.

BR: Yes, my boys went to the Philadelphia School, and they had a program where they went to the Schuylkill Center bi-weekly. I want to give props to the Philadelphia School because they gave my sons an excellent education, and I want my students to have those same experiences so that they can compete in the future.

Can I give props to a couple more people? Principal Hagan: she is a new principal to our school––last year was her first year––and she’s very supportive of this program. I want to say what an excellent job she’s doing: she has a heart for the students and for the community, and she’s extremely supportive of her teachers.

LG: And she loves this connection; she loves getting the kids outdoors. She is 100%.

BR: She’s incredible and she has so many ideas and new activities that she’s implemented at Patterson. We really are moving on and advancing with our school in a more positive direction. Also Mr. Steczak—he is our science teacher, and he is incredible. Whatever question anybody has about science, he will create an entire lesson. Once, we were learning about the Hoover Dam, the students said, “Oh, beavers build dams!” And I was talking to Mr. S about it, and he said, “Let’s make a dam!” So the students collected sticks, leaves, and small rocks, and Mr. S made a mud concoction and got paint trays, and the students worked with partners to build a dam across the width of the paint tray. Then we let it dry and put water on one side and we had to see which dams were able to hold water, or not. I’m learning to be like him!

What inspired you to become an educator?

BR: When I was about 11 or 12, I fell in love with this movie called Bustin’ Loose––it’s based in Philadelphia, starring Richard Pryor and Cicely Tyson. I knew when I saw it that I wanted to work with children in an urban environment. I was a social worker for a short time and I was also a TSS, a therapeutic staff support worker, but I decided that early childhood education is really what I love. First grade is where I’m meant to be [because of] that literacy component—I love seeing the students come in knowing letters and letter sounds but leaving reading paragraphs. I love to see that transition—that’s what inspires me to stay in first grade.

LG: I did not want to be a teacher. I’m the second person in my family to go to college: the first person was my uncle, who became a teacher! There were not a lot of options, and I really resisted even though everyone said, “You should be a teacher.” I did all kinds of other stuff, and when I was 39, my father died, and I sort of felt like, “What am I doing with my life?” I wound up going to grad school and being a classroom teacher, and feeling very dissatisfied with it. And I guess because my father had died, I got very interested in the kind of experiences I’d had with him, which were all outside. That’s where he and I connected, and I connected to my grandmother that way, through gardening and animals, and I realized I wanted to communicate that to kids.

I say to all the kids, “The Schuylkill River is your birthright! Clean air should also be your birth right, [Bartram’s Garden] is your birthright.” I’m hoping that kids get a little bit inspired—if you live on a block like mine, where there’s very little nature, what can you do to increase it? Or if you do live on a block where there are trees, how can we encourage that and appreciate it?

BR: I was just realizing how similar your childhood was to my childhood. My parents were from Philadelphia and when they got married, they didn’t want to raise me and my brother in Philly, so we moved up to New England. I was born in Massachusetts, and we lived there ‘til I was 4, then we moved to Concord, New Hampshire, and lived there ‘til I was 8. I was always a daddy’s girl, and he would take us canoeing and fishing and camping, and we always had a garden, either in our yard or in a plot of land that we rented—always doing something, always exposing us to new and different things. I want my students to experience that as much as possible.

I remember in Concord, New Hampshire, my first-grade teacher lived on a dairy farm and she took us to visit her farm. We were not only able to milk the cows, but we made homemade butter and baked rolls. At school, I remember sometimes, after a rain, she would take trash bags, rip them open, put them on us [like ponchos], and take us for nature walks. At recess, our playground was full of pine trees, and we would take the pine needles and build forts. I also remember a field trip to a nature center: at the center there was a creek. While walking along the creek, we noticed a beaver lodge. Memories like that I will always cherish, and I just want that for my students.

What’s your favorite fall memory in the Garden?

BR: I love when Leslie does lessons outside in the Garden: she’ll pull the easel out and the kids will sit on the mats, it’s a nice cool day and we’re just out in nature and experiencing nature together. I really enjoy going for the Color Walk: Leslie will give the kids paint chips and the kids have to find things in nature that correspond to the colors. When students see that maybe there’s a leaf that’s dying and it’s one or two shades darker, they can start classifying that.

LG: It gives them a focus—instead of seeing just a sea of green, they can start seeing different shades and noticing differences. If we’re talking about biodiversity, this variety matters—it’s not just about richness of experience but it matters for the pollinators, for the birds; it matters to the whole system. I want kids to start being able to appreciate that.

I have two favorite memories! One is rolling down a hill with this lady and her first-graders—she started it, not her students. It’s one of the reasons why I love her. Rolling down that tiny slope, we were going really fast! The other is from my first year here, teaching a first- or second-grade class from a Southwest school. It was November and it was a hard fall, so we were standing in the garden, and we could look down to the river because the trees were bare. And this little girl said, “This is the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.” That wide-eyed appreciation for that beauty was all her and that has stuck with me.

John M. Patterson School is a Philadelphia public school educating children in grades Pre-K–4, located at 7000 Buist Avenue in Southwest Philadelphia.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.