Ailanthus: John Bartram and Philadelphia’s Most Notorious Tree

Few trees define America’s urban environments more than Ailanthus altissima, or the “Tree-of-Heaven.” If you are not familiar with that name, you are undoubtedly familiar with the tree itself. Ailanthus is found throughout Philadelphia and every other major American city growing in all kinds of disturbed spaces: from vacant lots, to roadsides, to meadows and even between cracks in the concrete. It grows quickly and spreads quickly, making it one of the region’s most vigorous invasive species. To make matters worse, Ailanthus is extremely hardy, able to survive in poor soil and highly polluted air and is unappetizing to the herbivores who eat most trees.[1] Ailanthus is the tree that grows in Brooklyn in Betty Smith’s famous novel, and it is the preferred host for the city’s most notorious insect pest, the spotted lanternfly. Suffice to say, Ailanthus is one of the best-known plants in our region. But few know the story of its introduction and the Bartrams’ role in bringing this significant tree to America.

Ailanthus altissima is native to Taiwan and central China but was introduced to Europe by way of a Jesuit Priest named Pierre Nicolas d’Incarville, who sent seeds to Paris from Beijing in 1743. A few years later Peter Collinson, the English botanist and close correspondent of John Bartram, acquired some seeds from France that he grew in his garden in London. Although it is difficult to imagine given its noxious qualities today, eighteenth century botanists held Ailanthus in high regard, admiring its foliage, its perceived exoticism, and its toleration of urban environments. By the 1780s, it was a favorite in gardens across Europe and was widely planted in London and Paris, and it remained heavily used in urban landscaping through the nineteenth century.[2]

Foliage of Ailanthus altissima, the Tree-of-Heaven. Credit: Wikimedia commons.

Most sources credit Ailanthus’s introduction to America to William Hamilton, who maintained a botanical garden just about a mile up the Schuylkill of the Bartrams, at The Woodlands. Hamilton reportedly had Ailanthus seeds sent to his garden around 1784. But twenty years earlier, in 1764, John Bartram writes a letter to Peter Collinson where he describes the growth of a certain sumac species in his greenhouse:

“last summer there came up in my greenhouse from east India seed formerly sowed there an odd kind of Sumach (as I take it to be) it growed in A few months near 4 foot high & continued green & growing all winter & this spring I planted it out to take its chance it shoots vigorously & allmost as red as crimson”[3]

Most signs point to this plant being Ailanthus. The tree’s fast growth, hardiness in the winter, and red shoots are all characteristic of Ailanthus. The species is still sometimes referred to today as a sumac, although taxonomically it is no longer a member of the sumac genus. At the time the sumac genus, Rhus, included many different trees and shrubs with alternate compound leaves, like Ailanthus does. John Bartram would have been aware of all of the American sumac species, so if he is correct in recalling that he planted this from seeds brought from Asia (East India), then this very well could be the earliest recorded instance of Ailanthus in the Americas.

Peter Collinson, who was one of the first in Britain to receive Ailanthus via France, certainly thought that John Bartram had one in his greenhouse. He replied, describing his own plant:

“I have from China a Tree of surprising growth that much resembles a Sumach which is the Admiration of all that see it Phaps thine may be the same—It Endours all our Winters Thou Sayes thine came from the East but mentions not what Country: We call ours the Varnish Tree”[4]

The name “Varnish tree” refers to at least four different species of tree from Asia, and the 1750s saw intense taxonomical debate within the pages of the Royal Society of London’s Philosophical Transactions attempting to distinguish the different plants referred to by that name. English botanists were fixated on the so-called varnish tree because some species, like the Chinese Lacquer Tree or Japanese Wax Tree, had sap that could be turned into lacquer, a highly valuable substance that could be used for coating wooden furniture or artwork.[5]

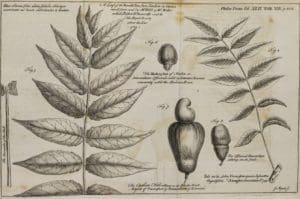

Ailanthus is similar to these species and became caught up in the craze over Varnish trees, and d’Incarville may have originally sent seeds of it back to Europe because he mistook it for one of those species. Upon receiving the seeds, English botanists quickly realized that they had several different species. John Ellis published a paper in Philosophical Transactions that distinguished a “Varnish tree” specimen found growing at two botanical gardens in London from other Rhus species, including a diagram that is the earliest botanical sketch of the plant.[6] To the dismay of botanists, this species did not have useful sap, although it was well-regarded aesthetically. Phillip Miller gives it the name “altissimum” in his Gardener’s Dictionary in 1768, and the tree was finally defined in its own genus, Ailanthus, by the French botanist René Louiche Desfontaine in 1788.[7]

The English botanist John Ellis used this drawing to argue that the “Chinese Varnish Tree” (figure 5) should be its own species. That plant later became Ailanthus altissima. Credit: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London.

But at the time John Bartram and Peter Collinson were looking at this curious tree from China, botanists still would have thought of Ailanthus as a type of Varnish Tree belonging to the sumac (Rhus) genus. Collinson described his Varnish tree as a “stately tree sent over raised from seed sent over from Nankin in China, in 1751, sent over by Father d’Incarville, my correspondent in China.”[8] This account lines up perfectly with John Ellis’s description of his new Rhus species, which modern botanists consider to be a description of Ailanthus.

Identifying plants from the historical record is never a straightforward task, and we cannot say for sure that Bartram’s tree was an Ailanthus without having a more detailed description or drawing of it. We can only speculate. Genetic research has suggested, however, that Ailanthus was indeed first introduced to North America through the Philadelphia area at the end of the eighteenth century, making either Hamilton or Bartram possible candidates for its introduction.[9] Bartram does not mention this plant again, so perhaps it died at some point and has no relation to the Ailanthus trees that are now widespread across the area. But given the tree’s propensity to spread and take root in even extreme conditions, it is not out of the question that it escaped Bartram’s greenhouse and later became naturalized in the region.

We have a few more references to Ailanthus from the years that Robert Carr was proprietor of the garden. Ailanthus appears in Robert Carr’s catalogue from 1828 as an exotic tree, priced at $1 compared to the 25¢ or 50¢ that most trees sold for.[10] In 1844, one of Robert Carr’s correspondents recalls an Ailanthus tree that was apparently given to Ann Bartram Carr as a wedding present in 1809. That tree was supposedly procured from Hamilton’s garden at The Woodlands and was still preserved at Bartram’s in 1844.[11] Both references point to Ailanthus not being widespread in Philadelphia in the early 19th century, but they do not rule out an earlier introduction during John Bartram’s lifetime.

Perhaps John Bartram, not William Hamilton, deserves the dubious designation of being the first to introduce Ailanthus to the Americas. We can only imagine what John Bartram would think if he saw what the little plant he found in his greenhouse in 1764 was up to today.

Notes

Cover image: Sketch of Ailanthus leaves by John Ellis, published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London in 1758.

[1] Patricia J. Wynne, “Ailanthus altissima”, Columbia Introduced Species Project, December 9, 2002.

[2] Shiu Ying Hu, “Ailanthus”, Arnoldia, 1979, 39(2): 29-50.

[3] John Bartram, Letter to Peter Collinson, May 1st, 1764; in The Correspondence of John Bartram, 1734-1777, ed. Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley (University of Florida Press, 1992).

[4] Peter Collinson, Letter to John Bartram, June 1st, 1764; in The Correspondence, ed. Berkeley & Berkeley.

[5] The Chinese Lacquer Tree is now Toxicodendron vernicifluum while the Japanese Wax Tree is now Toxicodendron succedaneum. Each of these species were considered part of the Rhus (sumac) genus at the time.

[6] John Ellis, “CXII. A letter from Mr. John Ellis, F. R. S. to Philip Carteret Webb, Esq; F. R. S. attempting to ascertain the tree that yields the common varnish used in China and Japan; to promote Its propagation in our American Colonies; and to set right some mistakes botanists appear to have entertained concerning It,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 49, (1755), pp. 866-876.

[7] Walter T. Swingle, “The early European history and the botanical name of the Tree of Heaven, Ailanthus altissima,” Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, Vol. 6, No. 14 (1916), pp. 490-498

[8] Peter Collinson, published in Hortus Collinsonianus: An account of the plants cultivated by the late Peter Collinson, compiled by Lewis Weston Dillwyn in 1843. Not published, printed in Swansea by W. C. Murray and D. Rees. Dillwyn believed that what Collinson thought was the Chinese Varnish Tree was actually Ellis’s new species, and cites his article in the Philosophical Transactions to support this.

[9] Preston R. Aldrich, Joseph S. Briguglio, Shyam N. Kapadia, Minesh U. Morker, Ankit Rawal, Preeti Kalra, Cynthia D. Huebner, and Gary K. Greer, “Genetic Structure of the Invasive Tree Ailanthus altissima in Eastern United States Cities,” Journal of Botany, vol. 2010.

[10] Robert Carr, Periodical Catalogue of Fruit and Ornamental Trees and Shrubs, Green House Plants, &c. Cultivated and for Sale at Bartram’s Botanic Garden, Kingsessing, Near Gray’s Ferry—Four miles from Philadelphia. Russell and Martien, Philadelphia, 1828, p. 21

[11] Dr. Steph. Browne to Col. Robert Carr, September 19, 1844, Society Misc. Coll, Box 7-B, Of644, 1842K, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.