An African Plant in Louisiana: William Bartram’s Encounter with Cleome gynandra

In October of 1775, William Bartram discovered a curious plant while voyaging through the bayous and cypress swamps of coastal Louisiana. While he was passing by the Taensapoa River along the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain, he stopped to rest at a small settlement that he recounted as “a few habitations and some fields clear and cultivated.” There, he found a pungent, flowering, and leafy herb that the locals had been growing in their fields. William described the plant as a member of the Cleome genus:

“Here are few habitations, and some fields cleared and cultivated; but the inhabitants neglect agriculture; and generally employ themselves in hunting, and fishing; we however furnished ourselves here with a sufficiency of excellent Batatas. I observed no new vegetable productions, except a species of Cleome, (Cleome lupinifolia) this plant possesses a very strong scent, somewhat like Gum Assafetida, notwithstanding which the inhabitants give it a place in soups and sauces.” [1]

William never mentions the plant again, but he must have taken some seeds of it back with him to grow at Bartram’s Garden, because the plant re-emerges in an illustration that he made for the book Elements of Botany in 1803. That illustration can clearly be identified as cat’s whiskers (modern name Cleome gynandra), which at the time Bartram named Cleome lupinifolia but later corrected to Cleome pentaphylla owing to its foliage that came in leaflets of five. The plant was still in cultivation at the Garden for some years after that, appearing in catalogues William Bartram compiled for interested botanists in 1807 and 1819, before it disappears from the historical record.

Unlike most other plants Bartram found during his expeditions, however, cat’s whiskers was not recorded anywhere else in the Southeastern United States, nor was it native to the region. Cat’s whiskers is actually native to the Old World. In many areas in Asia, locals treat it as a weed. But in many parts of Africa, especially eastern and southern Africa, the cultivation of cat’s whiskers as a leafy vegetable was (and remains) widespread.[2] At the time there was no evidence of anyone growing cat’s whiskers within thousands of miles of Louisiana.

How could William Bartram have found it on the shores of Lake Pontchartrain in 1775? Answering this question requires looking closely at the context he provides and at social histories of the region. Doing so gives a look into a lost piece of Louisiana cuisine and horticultural practice. Cleome gynandra shows that plants carry with them a social story that deserves careful investigation, filling in the gaps left by written records of the past.

We suspect that Bartram may have encountered a community that included free people of African descent who knew how to cultivate cat’s whiskers. Although Bartram does not give any more details on this community, we can infer that they probably were not of wholly European origin. Robert Hastings, in his The Lakes of Pontchartrain, speculates that the dwellings described by Bartram here were “apparently of European settlement.”[3] This was likely not the case, as the presence of Cleome gynandra would indicate.

When Bartram encountered European settlers, he usually identified their name and country of origin, as in the case of the “English Gentleman” named James Rumsey who Bartram had stayed with earlier that week. We know that Rumsey was deeply involved in the West Floridian slave trade. A fact that Bartram often tried to obscure in his writings, possibly owing to his own failed experience starting a plantation in Florida in 1766. Perhaps this is why no enslaved people are mentioned during his time at Rumsey’s.[4] But he does explicitly refer to Rumsey’s settlement (and other sites he visits) as a “plantation.” The settlement where he encounters cat’s whiskers is described with entirely different terminology, as “a few habitations” in a “fertile and delightful region.”

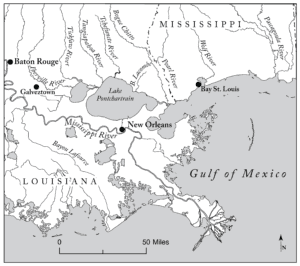

William Bartram journeyed along the northern shore of Lake Pontchartrain, eventually stopping at a fort along the Iberville River. Bartram found Cleome gynandra somewhere near the mouth of the Tangiapahoa river. Credit: Brad Sanders of the Bartram Trail Conference.

This part of Louisiana, which oscillated between British and Spanish colonial control, has been described by historian Frances Kolb as a “borderland” where all sorts of people sought to survive on the porous boundary between empires.[5] Indigenous Acolapissa and Choctaw people, many of whom were displaced by conflict with Britain during the Seven Years’ War, still lived on the north shores of Lake Pontchartrain and traded with colonial settlements. While Louisiana was under Spanish control, French Acadians and Canary Islanders flocked to the region. The period of British control brought a flood of European planters, who frequently brought with them enslaved African people, usually originating from West Africa.[6] And most importantly, the Louisiana borderlands were home to freed African Americans and Black Creoles, who sought whatever escape they could from a rapidly expanding slave system, sometimes even forming self-sustaining Maroon communities who lived on the outskirts of plantation society.[7]

The boundaries between these groups were blurred, since they intermarried throughout the eighteenth century.[8] Research on Louisiana Folklife by local historians has shown that so-called “swamp communities” on the northwestern side of the Lake persisted through the 20th century, where creolized families of mixed European, African and Native descent live fishing and hunting “virtually as did the Choctaw.”[9] That description lines up with evidence describing eighteenth century makeup of this part of Louisiana.

If Africans did indeed live at the settlement Bartram encountered, they could have brought with them the knowledge of how to cultivate and prepare Cleome gynandra. People in West Africa sometimes ate cat’s whiskers, especially during times of famine when they would foraged it naturally in disturbed or unsown fields. There, it may have been referred to as “boanga” or “mugole.”[10] Although most of the enslaved people in Louisiana came from Senegambia, which was not known to cultivate cat’s whiskers, there is evidence of the Birifor people of Burkina Faso preparing the leaves in sauces and soups, which matches William Bartram’s description.[11] Some enslaved people sold on the Gold Coast and transported to the Americas through the Middle Passage could have originated from that region.[12] They also could have come from another part of West Africa such as Nigeria, Ghana, or Benin where Cleome gynandra cultivation has been documented.

Photograph of wild cat’s whiskers growing in Tanzania. Credit: Dick Culbert, Wikimedia Commons

Cat’s whiskers would certainly not be the only plant to make its way from West Africa into the cuisine of Louisiana, where close contact between people of vastly different ethnic backgrounds led to a high degree of cultural diffusion. Enslaved people from West Africa would have found a climate and ecosystem suitable to growing many of the vegetables they grew at home. Okra, for instance, was brought to the region by people of African descent via the West Indies and became an important part of the region’s distinctive gumbo, while knowledge of rice cultivation came via the slave trade at the beginning of the eighteenth century and was quickly taken up across the region.[13] Perhaps Cleome gynandra is a forgotten part of this story of transcontinental cultural exchanges.

Slavery and settler colonialism cast a long shadow over early American plant science, and historians have documented how the labor of enslaved people and dispossession of Indigenous lands contributed to producing the profits that made empirical botanical research from people like the Bartrams possible.[14] William Bartram’s encounter with Cleome gynandra highlights an underappreciated part of this story, one that centers the contribution and agency of free Black Creoles in disseminating botanical knowledge.

Notes

Cover image: William Bartram’s engraving of Cleome gynandra for Elements of Botany in 1803.

Thanks to Joel Fry, whose research on Cleome gynandra made this article possible; and Brad Sanders, who created the map used here.

[1] Bartram, William. The Travels of William Bartram, Naturalists Edition, annotated by Francis Harper, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1958), 269.

[2] Chweya, James A. and Nameus A. Mnzava. “Cat’s whiskers. Cleome gynandra L. Promoting the conservation and use of underutilized and neglected crops,” Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research, Gatersleben / International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy, 11. Chweya and Mnzava list nearly 40 countries that C. gynandra is likely native to.

[3] Hastings, Robert W. The Lakes of Pontchartrain: Their History and Environments, (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2009), 45

[4] McGaughy, Taylor. “Bartram’s Westerly Wanderings: Economic Transitions in Travels”. In The Attention of a Traveller: Essays on William Bartram’s Travels and Legacy, ed. Kathryn H. Braund. (University of Alabama Press, 2022), p. 17. See Sharece Blakney’s blog post titled “Six Likely Negroes: John Bartram and the East Florida Plantation” to read more about William’s past with slavery.

[5] Kolb, Frances. “Profitable Transgressions: International Borders and British Atlantic Trade Networks in the Lower Mississippi Valley, 1763-1783,” in Atlantic Environments and the American South, ed. Thomas Blake Earle and D. Andrew Johnson (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2020), 135-54.

[6] Usner, Daniel H. “‘A Prospect of the Grand Sublime’: An Atlantic World Borderland Seen and Unseen by William Bartram,” in The Attention of a Traveller: Essays on William Bartram’s Travels and Legacy, ed. Kathryn H. Braund. (University of Alabama Press, 2022), 22.

[7] Reeves, William D. Historic Louisiana: An Illustrated History. (San Antonio: Historical Publishing Network, 2003), 11-12.

[8] Gardner, Joel. “The Florida Parishes: An Overview,” In Folklife in the Florida Parishes. (New Orleans: Louisiana Division of the Arts, 1988).

[9] Gregory, H.F. “Indians and Folklife in the Florida Parishes of Louisiana,” in Folklife in the Florida Parishes. (New Orleans: Louisiana Division of the Arts, 1988).

[10] Chweya, James A. and Nameus A. Mnzava. “Cat’s whiskers,” 10.

[11] Freedman, Bob. “Cleome gynandra.” Purdue University Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture’s Famine Foods Project. https://www.purdue.edu/hla/sites/famine-foods/famine_food/cleome-gynandra/. Accessed 6-2-2022.

[12] Slavery and Remembrance Project, 2022. “Slave Trade Routes”. Published by The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and UNESCO’s Slave Route Project.

[13] Brasseaux, Carl A. The Founding of New Acadia, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987).

[14] McGaughy, Taylor. “Bartram’s Westerly Wanderings: Economic Transitions in Travels”. In The Attention of a Traveller: Essays on William Bartram’s Travels and Legacy, ed. Kathryn H. Braund. (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2022), p. 18.